Local Voices

Norfolk’s Slave Trade Largest On East Coast

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

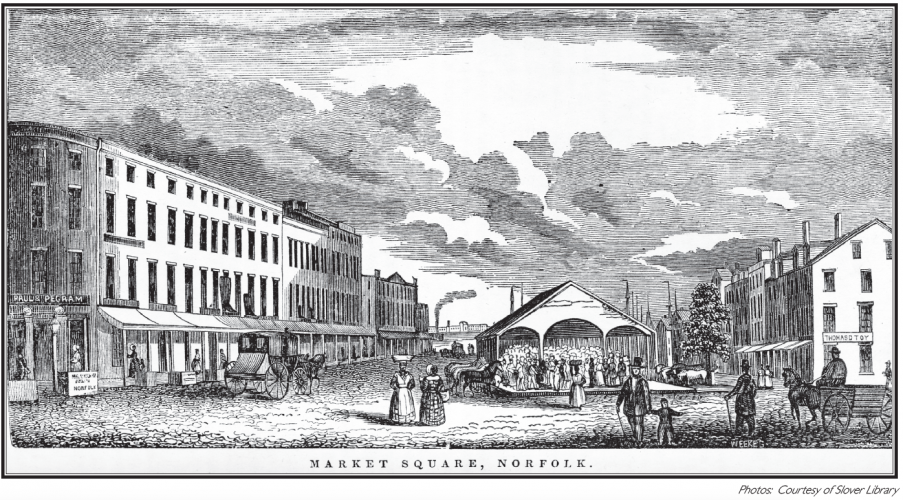

Today, Bank Street flows through the Commercial Place section of downtown Norfolk, the heart of the city’s oldest business and commercial district.

Until the company leaves, the city’s lone Fortune 500 company, Norfolk Southern, is housed in its headquarters in the area.

Its towering neighbors house the operations of banks, investment traders, financial specialists, lawyers, planning and other technical professionals which power the city’s economic engine.

The Icon Building, now one of the city’s newest and tallest residential complexes sits on Bank Street. It is the home of a young and talented workforce manning offices and cubicles in nearby buildings and elsewhere.

The City Hall, court buildings and detention center and other government complexes sit near the area.

There are destinations for entertainment, shopping, and visiting tourists, such as the MacArthur Center, Waterside along the waterfront, Nauticus, and hotels like the Main, sitting near the Granby Street artery alongside eateries and other enterprises.

But 211 years back to 1808, we would see an earlier version of this 21st century Norfolk.

Banks, entrepreneurs, bureaucrats, merchants, lawyers, and residents inhabited the same steel and glass towers space, but as wooden and some brick structures.

Each morning on the Merchant Square, as it was called in 1808, merchants would open their storefronts. Day traders –farmers – would place on stands valued produce, meats and other wares to display for patrons to buy directly or bid on.

In 1808, as now, commercial, military and leisure use of the Elizabeth River was a major component of the city’s economy. Massive amounts of valuable commodities as cargo traversed the river with vessels bound for domestic and overseas ports.

At the same time, an even more valuable commodity was locked away and secured at various places nearby. It was not horses or hogs ready to be sold as beasts of burden, to plow fields, to breed new stock or to be slaughtered for the table.

Instead, it was enslaved men, women and children of African descent, stored away in jails and pens to be bought and sold.

They were the source of manpower which would generate fortunes for the white farmers and merchants. Their offspring assured a future source of labor and wealth.

The biggest of the pens or jails was owned by William W. Hall. It was located on the well-groomed green space next to Norfolk’s current City Hall Complex.

Before it was torn down two years ago, the city’s Circuit Court building stood on the spot before a new one was built a short distance away facing St. Paul’s Blvd.

There were other slave pens, including one located in a space between the current Waterside Festival Market and the Sheraton Hotel.

Freshly imported from inland plantations or off ships from domestic ports, Black slaves stood on the auction block and were inspected by would-be buyers.

As chattel or property, they belonged to individuals and family estates and were auctioned off to settle debt or they were excess commodities to generate income for the bereaved family.

Still standing, but built in 1850, is the old domed Norfolk City Hall/Court House which is now a museum where General Douglas MacArthur and his wife are buried.

At one time, it was customary for Black slaves to be sold on its steps to settle civil judgements or for persons to liquidate their estate by court order.

Slave traders such as Hall or Charles Hatcher, according to old Norfolk maps, and extracts from the old Guaranty Title and Trust company deed abstracts, had their offices near Newton’s Wharf, where ships waited nearby to have their valuable cargo placed on them.

Before the city devised land maps, these ledgers are today one of the best means of looking back at the early 1800s and tracing the location of real estate – which was used as slave jails (called Negro Repositories). Also, the offices and homes, deeds and property holdings of the slave merchants, lawyers and others involved in the trade.

The slaves were placed on ships docked primarily at Campbell’s Wharf (later renamed Ferry Landings) and Mardsen’s Wharf (later called Roanoke Docks) once located on the eastern section of Norfolk’s Sheraton Hotel and Waterside respectively today. There were others located up and down the city’s waterfront where slave ships docked awaiting to transport their valuable Black Cargo.

Research being compiled by history researchers at the Slover Library’s Sergeant Memorial Collection illustrate the significant role Norfolk played as an export center during the domestic slave trade starting in 1808 until the city was conquered by Union forces in 1862 during the Civil War.

In Norfolk, valuable records at its customs houses were destroyed by fire in the early 1800s which would reveal the number of Black slaves load on and off ships.

So over the past nine years, the researchers have plied through old property deeds, newspapers advertisements, the few manifests of ships bound for New Orleans and other destinations, records on ancestry, and sites in New Orleans to bring light to Norfolk’s role in the domestic slave trade.

Slaves were property so they were listed on business ledgers of owners, as they would livestock. The heirs of slave owners were bequeathed slaves via wills: another source of information.

Their letters, billing receipts or ship manifests all have valuable bits of information that can be compiled to give a clearer picture of slavery in Virginia.

Virginia was a slave breeding and exporting powerhouse during the height of the domestic slave trade.

Based on the work of staff at the Historic New Orleans Collection, the recorded slave shipments by ship collectively from Richmond, Alexandria, Petersburg, and Norfolk to New Orleans totaled 37,343 slaves.

Of that total, Norfolk exported 21,000 from the city via ship to New Orleans, thus making Norfolk the main port in the Upper South for exporting slaves by ship to the Deep South. Richmond, which also had a seaport and prosperous slave market operation shipped 8,000 and Baltimore 12,000.

If not put aboard ships bound for ports further south, these valuable slaves were transported on foot, “two by two” overland in human trains called “coffles” to near and far areas to work on plantations.

…see Evolution, page 3A