Black Arts and Culture

Black History Music: The Roots of Black Art & Entertainment

“Dive into the rich tapestry of African-American art and entertainment, particularly the profound influence of music. From spirituals sung by slaves to the roots of gospel, blues, and the birth of hip hop, Virginia’s music history echoes the resilience and creativity of its Black community.”

#BlackHistoryMonth #AfricanAmericanArt #MusicHeritage #VirginiaHistory

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter Emeritus

New Journal and Guide

“African-American Art and Entertainment” is the theme of the 2024 edition of Black History Month (BHM). It is influenced by the diaspora of Black people from the African Continent to the Caribbean, South Americans, and the Black American experience.

“African-American Art and Entertainment” is the theme of the 2024 edition of Black History Month (BHM). It is influenced by the diaspora of Black people from the African Continent to the Caribbean, South Americans, and the Black American experience.

The African-American influence has been paramount in visual and performing arts, literature, fashion, folklore, language, music, architecture, culinary, and other forms of cultural expression.

African-Americans used art to create culture, preserve history and community memory, and empower. Artistic and cultural movements, such as the New Negro, Black Arts, Black Renaissance, hip-hop, and Afro futurism, have been led by people of African descent and set the standard for popular trends around the world. In 2024, we examine the varied history and life of African-American arts and artisans.

For centuries, Western intellectuals denied or minimized the contributions of people of African descent to the arts as well as history, even as African artistry in many genres was mimicked and or stolen. There is an unbroken chain of Black art production from antiquity to the present. The chain links to the New World began in Central Africa, Egypt, and Europe.

One of the links was music and Africans in the Americas. In Virginia, where the first Africans appeared in an English Colony, despite enslavement, Blacks contributed their cultural genius to cultivating musical traditions.

enslavement, Blacks contributed their cultural genius to cultivating musical traditions.

Recently, at the Slover Library in Norfolk, Dr. Gregg Kimball, former Director of Public Services and Outreach at The Library of Virginia, provided a multimedia presentation of the evolution of Black and other music genres in Virginia and this region.

Kimball featured rare photographs and period recordings highlighting some of the region’s significant stars and its most important musical contributions.

Initially, Kimball paid tribute to the pre-colonial musical traditions of the indigenous peoples of the 11 ‘recognized’ tribes, particularly the Nansemond Tribes of this region.

Kimball said natives had “their own sounds” musically and instruments such as “a long cane flute, rattles or drums used during pow-wows,” which created a terrible noise to the ears of the white colonists.

The drum circles and instruments are still heard today during the Nansemond tribes’ annual pow-wow in August.

Kimball noted the legacy of Black musical creation occurred at the same time when the English imported Black people to be slaves in Virginia.

He said Black slaves became skilled at playing the fiddle or the violin. The difference, he said, between the two “was who was playing it.”

In Africa, he said, a string instrument called the Akonting existed. Its descendant, the Banjo, was used by slaves in the colonies to create music.

During estate sales in this area, when slaves were sold, their mastery of musical instruments such as the violin was included in the list of their skills.

He said if they escaped, the master posted notices indicating many Black male slaves “may possess an instrument” like a violin.

Black slaves provided the music and dances for Christmas parties and other events in “the Big House” or corn shucking. The tunes were created in England or of the slaves’ own creation.

The early music of Virginia included the spirituals sung by slaves as a means to cope with the brutal work in the fields or worship services away from whites, which would restrict them, fearing slaves were plotting rebellions.

Kimball said that examples of those spirituals were captured in the 1930s at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) by Professor Roscoe Lewis for the Work Progress Administration (WPA), who recorded former slaves singing them in this area and in Petersburg for the Library of Congress.

***

After the Civil War, former slaves formed churches and other institutions, such as the first public schools and colleges, to illustrate their desire for an empowering community.

On the Virginia Peninsula, Black former slaves who collected in Hampton and around Fort Monroe before the end of the war created Hampton Institute. It formed its version of Jubilee Singers, akin to the one at Fisk. Whites were fascinated by music, and the schools used these groups to benefit themselves.

Kimball said educated Black music teachers trained at Virginia Union taught their students to perform more refined or “concertized” versions of the spirituals than those sung by the Black field hands.

The Hampton Jubilee Singers and a Quartet traveled throughout the nation, representing the school and raising money to operate and construct buildings such as the historic Virginia Hall on that campus.

Dr. Kimball explained that the Black Worship services gave birth to the Spirituals and, later, the Gospel and talent.

***

The first Black musical superstar, Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones was born in 1868 in Portsmouth, Virginia. Her family later moved to Providence, Rhode Island. Her father opened an AME church where she performed until she enrolled for training at the Providence Academy of Music and the New England Conservatory of Music to become a soprano.

She made her professional debut in 1888 in New York and emerged as the highest-paid Black artist in the nation by the end of the 19th century.

Due to Jim Crow segregation, she could not perform in many white-owned venues. But she did perform at the Norfolk Music Academy, controlled by whites, and received high regard.

She was the “Black Patti,” called so after white Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. She did not like it, but she used the title to promote her performances of grand and light opera and popular music. She performed in the West Indies, South America, Australia, India, southern Africa, and Europe.

Kimball said Jones returned to her native Portsmouth yearly and performed at area churches. Unfortunately, Kimball said, her work and that of many other Black artists was not recorded.

Fortunately, many historians gather information about such artists at that time from the pages of the Black Press.

By the 1920s, Black artists often performed secular music, like the emerging Blues genre, on street corners. An example was Norfolk’s James Simmons, better known as “Blues Bird Head,” was accompanied by the Harmonica and Piano. According to a 1931 article in the Norfolk Journal and Guide, he could make his harmonica cry, smile, and sigh” in recordings he made in 1929.

Many of these artists made it northward from Norfolk to big-time stardom as part of the Black migration.

At the same time, artists used their popularity and newfound wealth to promote social activism against Jim Crow.

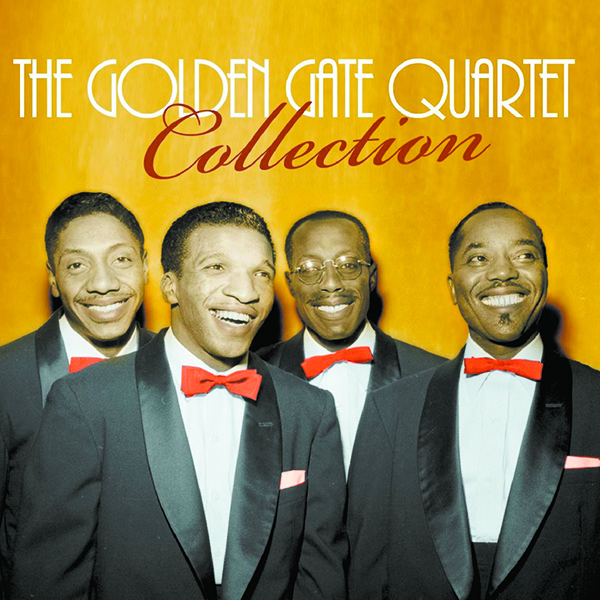

The Gospel-Blues music tradition, Kimball said, spawned “hundreds of mostly male Gospel Quartets” throughout the region. They were based in churches around the area, and most were never recorded. Pictures of them do exist in the Library of Virginia.

Groups such as the Suffolk Jubilee Singers, The Jazz and Jubilee, Silver Leaf, and Golden Gate Quartets of Norfolk performed from 1919 and decades later became nationally known.

The Norfolk Jubilee Quartet had a smash hit called the “Queen Street Rag.” Queen Street is now Brambleton Avenue.

The quartet’s vocal technique was the basis of doo-wop, rock and roll, jazz, and R&B and Soul music groups around the world years after.

“The slave era Spirituals, Blues, Gospel, and early jazz are the roots of the music we enjoy today. It was crafted here in Virginia and notably in Hampton Roads,” said Kimball.

“Today, you see Hip hop artists and groups sampling the works of Soul artists such as James Brown and early jazz artists who built their artistry on these building blocks.”

You may like

-

TAM Awards $1000 Scholarship To Soprano Lillian M. Parker

-

Film Review: Bad Boys: Ride or Die

-

First Black Racer in Porsche Carrera Cup Competes at Formula One Miami Grand Prix

-

Negro Baseball League Statistics Elevated In an Historic MLB Move

-

Bookworm Review: The Black Girl Survives in This One

-

Film Review: Bob Marley: One Love