Black Arts and Culture

Black History Month 2024: “Chitlin Circuit” Was Pathway To Black Fame Under Jim Crow

Explore the transformative journey of Black entertainment from the era of the Chitlin’ Circuit to the modern-day global stage. Discover how artists like Beyoncé and Pharrell Williams continue to shape cultural movements and drive significant economic impact through their groundbreaking performances.

#ChitlinCircuit #BlackEntertainment #EconomicImpact #Beyonce #PharrellWilliams

By Rosaland Tyler

Associate Editor

New Journal and Guide

When segregation was legally banned in the 1960’s, once-thriving Black segregated theaters and performance halls in Hampton Roads and elsewhere began to slowly shutter their doors.

From the 1930s until the 1960s, these venues were part of the so-called “Chitlin’ Circuit, a network of Black-owned nightclubs, dance halls, juke joints and theaters in the South, on the East Coast and parts of the Midwest which provided entertainment for Black audiences.

But would the demise of the so-called Chitlin’ Circuit birth a new economic system for Black artists and entertainers? It did not seem possible at the time. But did these closures actually pave the way for Black artists like Beyoncé and Pharrell Williams? Both artists recently launched highly profitable concerts, due to the fact that these two wildly popular Black artists were no longer restricted to performing in Chitlin’ Circuit venues.

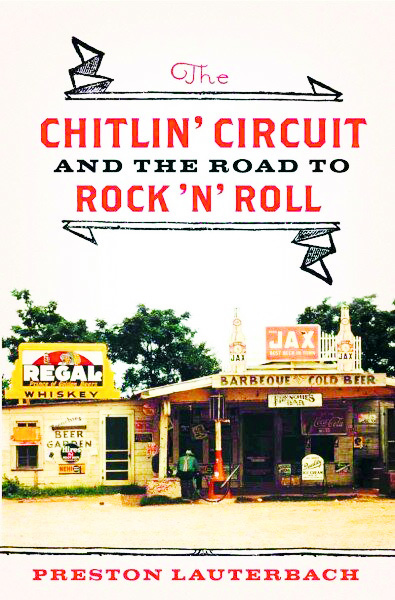

“Traveling musicians could come into a Black community, play, make money and go to the next town,” author Preston Lauterbach wrote in, “The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll” in 2011.

Lauterbach’s award-winning book was the first history of the network of Black juke joints that spawned rock ‘n’ roll. It establishes the Chitlin’ Circuit as a major force in American musical history through firsthand reporting and historical research.

It is impossible to list the number of Black entertainers who launched their careers and impacted society on the Chitlin’ Circuit. But Sammy Davis, Jr., Harry Belafonte, Aretha Franklin and Tina Turner said their careers began on the so-called Chitlin’ Circuit. The same applies to the skyrocketing careers of Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Muddy Waters, Ray Charles, B.B. King, and Marvin Gaye.

The single thread that runs through the histories of these famous Black entertainers stretches back to a booking agent called Theater Owners Booking Association, or TOBA, a network of theater owners. In other words, TOBA controlled most Black-owned, operated and patronized venues during the Jim Crow era.

“Some were juke joints with dirt floors,” USA Today noted in a 2021 series titled, “Hallowed Sounds.”

While some Black artists performed in barns, “some filled dance halls and some ripped four gigs a night at polished theaters ready to overflow with a toe-tapping escapism that washed away hardships that waited just outside the door,” according to USA Today.

“Many of these halls would eventually shutter. But some, such as the Apollo Theater in New York City, Royal Peacock in Atlanta or the Dreamland Ballroom in Little Rock, still stand today – brick-and-mortar vestiges of the art created decades earlier.”

Drinks were cheap. Tickets cost $1.

“People “would work their asses off all week,” said Alan Leeds, a music industry veteran who cut his teeth working for James Brown on the Circuit. “When Saturday came, you really wanted to relieve the stress.”

Although the Chitlin’ Circuit has disappeared, Leeds said, it once “was a necessary step…When they came out on stage, they brought you something you’d never seen.”

James Brown, for example, performed at least 51 weeks on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Leeds said. “He never lost sight of the fact he was doing this to make a living. Yes, it was artistic in the sense that you were making great music … but, financially, you were still struggling to support the system that you wanted and needed for your art.”

Still, the ‘Chitlin Circuit’ was not luxurious or glamorous. “You’d go into a town and you’d find somebody nice enough to fix a dinner for you and let you sleep in a bed,” said Bobby Rush, a Grammy Award winning Mississippi guitar player, who performed on the Chitlin Circuit. “You’d put some mattresses on the floor … or you’d sleep in your car. That’s what we had, man, and we didn’t think nothin’ about it.”

This is the point. Performers such as B.B. King, Jimi Hendrix, Muddy Waters and Ray Charles became household names, perfected their skills and changed local economies, as well as today’s music scene via the all-Black Chitlin’ Circuit.

But think about it. Were (now largely bygone) Black artists (unknowingly) paving the way for modern-day singers such as Beyonce, who recently earned an estimated $570 million for her 56-date Renaissance worldwide tour that kicked off in May 2023 in Europe, and proceeded to North America?

According to Digital News, “Her five sold-out shows at London’s Tottenham Hotspur Stadium marked a historic moment, as no one has played so many shows at the stadium since its opening in 2019. An impressive 238,000 fans were in attendance across all five shows to see one of the most celebrated performers alive.”

Similar to how Chitlin’ Circuit artists generated income for minimum wage workers employed at nearby movie theatres, restaurants, hotels and stores in Black business districts during the Jim Crow era – did Beyonce’s recent tour perform a similar feat?

Kendrick Lamar in Los Angeles performed a remix of “America Has a Problem.” Megan Thee Stallion performed “Savage Remix” in Houston. Beyonce’s 11-year-old daughter Blue Ivy performed.

Anything Beyonce does become “a cultural movement,” the New York Times noted.

In October, when Beyonce wrapped up her world tour on Oct. 1, in Kansas City, she had earned at least half a billion dollars in ticket sales, according to Forbes.

Pharrell Williams, meanwhile, estimated that the economic impact of his “Something in the Water” concerts in Virginia Beach resulted in millions flowing into Virginia Beach.

“The 2019 event created about $24 million statewide in wider economic impact – things like hotel bookings, restaurant sales and the like,” according to WHRO. “This week’s analysis by Virginia Beach staff indicated the festival’s impact this year was around $27.7 million overall with around $1.5 million in city tax revenue.”

In 2019, hotel occupancy for the region for the weekend of the festival was 86 percent or higher, according to a joint report from Old Dominion University and the city.

Subsequent reports showed Williams’ local concerts have generated a steady revenue increase in Virginia Beach.

“In 2021, Virginia Beach officials said the city experienced record-breaking economic success and the festival had a total economic impact of over $24 million on both Virginia Beach and the surrounding region,” according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.