By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

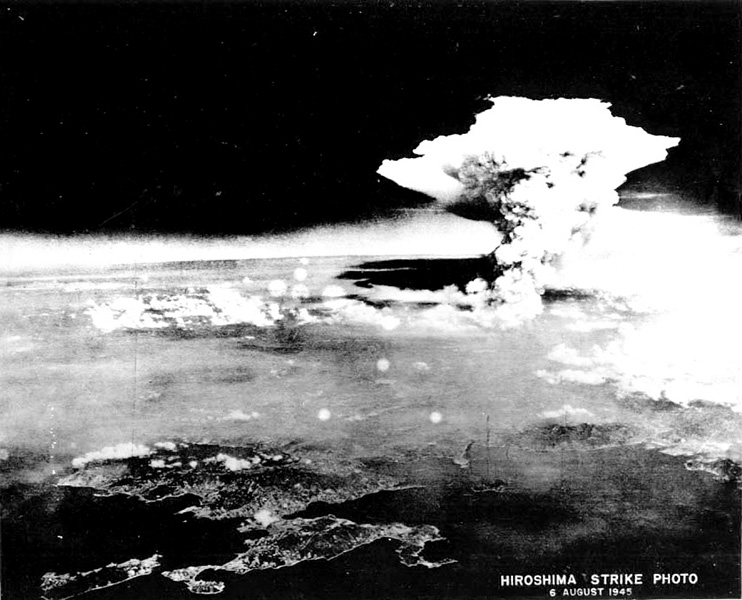

Seventy-eight years ago, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6; three days later the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

The two incidents forced the Japanese to surrender and thus ending WWII and the U.S. conflict with that nation.

This was the only time such powerful and destructive weapons have been used.

One of the box office blockbusters in this summer’s movie season is “Oppenheimer,” depicting the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American theoretical physicist and Director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory which developed the technology and built the deadly weapons.

He was born in 1904 in New York City to Jewish immigrants who exited German before the Nazis rose to power.

The Harvard-trained scientist is defined as the “father of the atomic bomb.”

The movie depicting his life and trials has grossed over $500 million.

While Hollywood is celebrating the life of Oppenheimer on the silver screen, Norfolk and Virginia have an “Unsung Hero” who also made contributions to the creation of the atomic bomb and later equipment used to detect the deadly byproducts of atomic material.

His name is Robert J. Omohundro.

Omohundro was born and raised in Norfolk, Virginia in 1921.

The future Physicist was one of a select few African-American scientists and technicians to work on the Manhattan Project and thus contribute to the development of the atomic bomb during World War II.

Omohundro, according to his Bio and articles in the GUIDE, was one of 19 African-American scientists who worked on one part of the project or another.

In 1941, in the first example of Affirmative Action and in order to spur employment opportunities for Blacks, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which stated that “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense of industries of Government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

The Manhattan Project did create opportunities for Black Americans’ advancement, but many Black workers grappled with Jim Crow segregation.

There were 179,000 people who were hired for the project overall.

But with the exception of these few highly trained scientists, most of the Black workers at Oak Ridge and Hanford, which were the sites of several huge Manhattan Project facilities, took on jobs as construction workers, laborers, and janitors.

The eldest child of Henry Omohundro and Brownie Pierce Omohundro, Robert had one sister, Gladys, and four half-siblings, Joseph, Mildred, Annie Mae, and Dorothy from his father’s first marriage.

Omohundro graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk, in 1939 and then earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a master’s in physics from Howard University in Washington, D.C.

After graduation, he worked as a radio tester with the Western Electric Company.

Omohundro’s contribution to the atomic bomb project was his work as a mass spectroscopist. Mass spectrometry (MS) is a technique that scientists use to help identify particles in samples by their mass.

During World War II, Omohundro, who worked at a secret test facility in Arizona, was also responsible for developing devices to locate and measure radiation emissions from atomic warheads.

These devices were used long after World War II by the International Atomic Energy Agency in airports around the world to detect clandestine transfers of fissionable material and portable neutron detectors.

From 1948 to 1984, Omohundro applied the techniques of nuclear physics honed during his work on the Manhattan Project to developing technology at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C.

He was noted for his development of devices that prevent the propagation of plutonium at airfields. In addition, he continued his World War II research by designing more advanced devices for radiation detection from nuclear warheads.

In 1963 and 1971, he obtained two patents in the field of nuclear physics. Over the course of his career, Omohundro authored and co-authored 40 scientific articles.

Omohundro was a member of many professional associations and groups, including Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity.

Robert Johnson Omohundro died of cardiac arrest at George Washington University Hospital on May 15, 2000, in Washington, D.C. He was 78-years-old.

Most Black and White scientists who contributed to the “Manhattan Project” had to keep their activities a secret.

So only in the last two decades has information about Omohundro and other Black professionals been fully released to the public.

One of them was Dr. William Jacob Knox, Jr., a chemist with a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work on uranium separation was crucial to the development of atomic bombs. Knox became the Manhattan Project’s only Black supervisor after he was appointed to lead the all-white Corrosion division of the project at Columbia University.

Another was a 21-year-old mathematician named Jesse Ernest Wilkins, who joined the University of Chicago’s Met Lab to research plutonium in 1944. A child prodigy, he was admitted to the University of Chicago at 13-years-old, Wilkins earned his Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Ph.D. in just six years.

Another Black scientist, Samuel Proctor Massie, Jr. of Arkansas, began work as a research assistant for the Manhattan Project in 1943 at Iowa’s Ames Laboratory, converting uranium isotopes into liquid compounds. After the war, Massie completed his Ph.D., and taught at Langston University in Oklahoma.

The contributions of these men and other Black scientists like Jasper Jeffries, Carolyn Parker, and Moddie Daniel Taylor were crucial to the Manhattan Project.

Like this:

Like Loading...