Black History

Clinton 12 (Tenn): First Blacks To Break School barriers in the South

Explore the courageous journey of the Clinton 12, who broke the Jim Crow barrier in 1956, paving the way for school desegregation in the South. Their resilience against segregationists changed history. #CivilRights #SchoolDesegregation #Clinton12 #CivilRightsHistory

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

In a span of five years, after the U.S. Supreme Court declared racially segregated public education illegal, history was made when the first Black students enrolled in previously all-white schools.

Many southern states had written laws in their Constitutions outlawing school desegregation, but the Brown Decision in 1954 was designed to dismantle that system.

In Norfolk, the Norfolk 17 made history by entering six all-white schools in February of 1959.

Two years earlier, on September 25, 1957, the Little Rock 9 wrote a passage in the history books after challenging white resistance to enroll in Central High School.

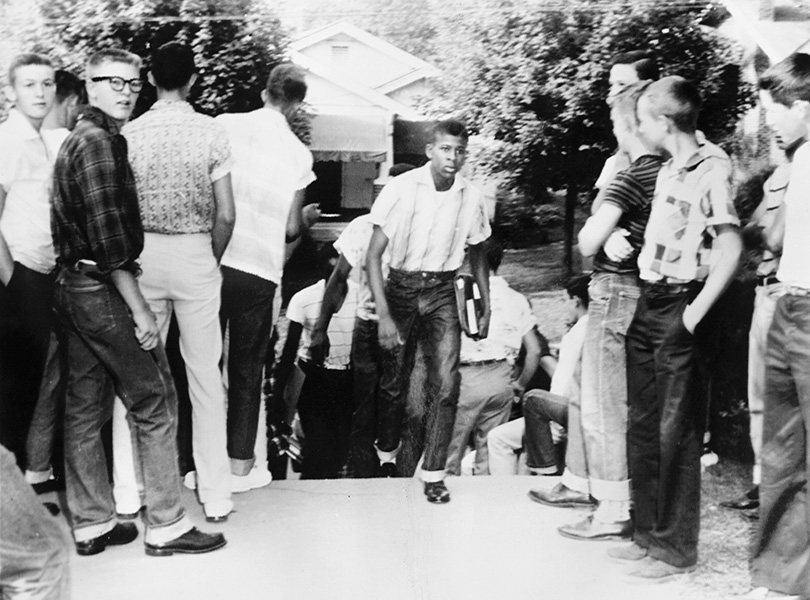

But the very first Black students in America to break the Jim Crow barrier in a southern state occurred 67 years ago this month in 1956 with the “Clinton 12” in Clinton, Tennessee.

As in Norfolk and Little Rock. The Clinton 12 were targets of discrimination and violence for attending the all-white Clinton High School, which caused some of them to leave the school and move to other states.

Out of the original 12, only two students graduated.

The twelve original students were Jo Ann Allen, Bobby Cain, Anna Theresser Caswell, Gail Ann Epps, Minnie Ann Dickey, Ronald Gordon Hayden, William Latham, Alvah Jay McSwain, Maurice Soles, Robert Thacker, Regina Turner, and Alfred Williams.

The story of the Clinton 12 included five years of legal and civic confrontation between the Black community and the forces that sought to avoid compliance with the Brown Decision.

The news was recorded by the majority press and the Black Press, at that time, including the Norfolk Journal and Guide.

Over the years, the story has been depicted in several books and the most recent is “A Most Tolerant Little Town: The Explosive Beginning of School Desegregation” by Rachel Louise Martin.

In 2017 the Tennessee Historical Society released an online article on the issue.

A series of events from 1947 to 1958 placed the Civil Rights story of Clinton, the seat of Anderson County, near Knoxville, on the national stage as one of the starting points in the modern Civil Rights movement.

In August 1950, four Black youths who were eligible to attend the all-white Clinton High School attempted to enroll but were rejected by school officials.

In 1950 a group of citizens filed a lawsuit, McSwain et al. v. County Board of Education of Anderson County, Tennessee. It was heard in February 1952, in the U.S. District Court of Knoxville. Carl A. Cowan of Knoxville, a respected Black attorney, and Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund led the legal team.

In his ruling of April 1952, Judge Taylor denied the lawsuit and upheld the position of the county school board.

Two years later the Brown decision declared segregation unequal.

Local government officials moved to upgrade all-Black schools, to placate Black parents and avoid compliance.

An integration plan was developed, too, to delay compliance.

Then, in January 1956, Federal Judge Taylor ordered the school board to end segregation by the fall term of 1956.

According to the online article, there was no white resistance that summer. Registration of the 12 African-American students took place without incident on August 20.

But days later, segregationists began to rally many white citizens to resist the court order.

Two days before classes, John Kasper, executive secretary of the Seaboard White Citizens Council, arrived and organized it.

On Monday, August 26, 1956, the “Clinton 12” made history by walking down Foley Hill where they lived to desegregate a state-supported in Tennessee and the South.

The first day was without incident, but the very next day crowds, threats, and violence, led by Kasper, exemplified white resistance.

When Federal Judge Taylor issued a temporary restraining order, forbidding Kasper and his followers from interfering with school integration, they ignored the order. The judge then ordered federal marshals to arrest Kasper for criminal contempt of court. On August 30, he gave Kasper a one-year sentence.

Taylor’s decision was the first to implement the Brown decision.

Kasper was replaced by another white resister, Asa Carter, a White Citizens Council leader from Birmingham, who kept the tension high among the resisters.

On Labor Day Weekend, September 1-2, 1956, riots broke out, with cars overturned, and windows smashed.

Whites took over the town, threatening to dynamite the mayor’s house, the newspaper, and the courthouse.

Dynamite was thrown about in the Black neighborhoods.

The police force was overwhelmed, and city officials asked Governor Frank G. Clement for help.

Residents formed a “Home Guard” to protect property and lives from the white mob until state assistance could arrive. Six hundred guardsmen arrived, and the worst of the violence ended.

The use of the National Guard by Governor Clement was another first in the Civil Rights movement and remained until the end of September.

Would the governor continue to use the Guard or refuse to activate the Guard (the situation that occurred in Little Rock, Arkansas, the following year)? He did activate highway patrolmen and National Guard forces to maintain the peace and keep the roads open in Clinton.

Segregationists across Tennessee decried Clement’s decision, but as the news from Clinton received national and international attention, other Tennesseans praised the governor’s decision to intervene.

But segregationists continued burning crosses on the lawns of some high-school faculty and civic leaders who supported integration.

As the intimidation escalated, shots were fired at the home of two Black students attending Clinton High School, and dynamite blasts punctuated the peace of the county.

Tensions continued in spite of the state’s intervention, especially once a slate of pro-segregationists challenged city incumbents in municipal elections.

The segregation of the schools was the only issue. Harassment and threats escalated against the Black children, property, and their institutions to the point that the Black parents met at Green McAdoo School and decided they could no longer send their children to the white school.

Then, in an amazing turn of events, a white Baptist minister, Reverend Paul Turner, pastor of the First Baptist Church, and others escorted Black students to Clinton High School on December 4, 1956, the day of municipal elections.

Reverend Turner and others escorted them down Foley Hill to the white high school, creating in effect a white human shield to protect and reassure the Black students.

Once the three white leaders left the students, a white mob severely beat Reverend Turner on his way to First Baptist Church. In reaction to the attack on Turner, and other threatened violence, Principal David J. Brittain closed the high school and did not reopen it until December 10.

In December 1956 and January 1957, the media converged on Clinton.

CBS TV’s Edward R. Murrow produced one of his famous “See It Now” programs on Clinton, titled “Clinton and the Law.” The process of desegregation in Clinton became national and international news throughout the spring of 1957.

The following spring, Gail Ann Epps became the first African-American female to graduate from a publicly integrated high school in Tennessee. On Sunday morning, October 5, 1958, Clinton High School was bombed and was destroyed.

But with the assistance of evangelist Billy Graham, columnist Drew Pearson, and a host of local citizens, the school was rebuilt.

The desegregation of Clinton High School in 1956-58 was not replicated at the city’s primary grammar school for African-Americans. However, not until 1965 would the ten-year struggle to desegregate public education in Clinton and Anderson County end.

You may like

-

Is Kamala Harris Following Footsteps of Other Trailblazing Female Leaders

-

Solidarity in Action: Black Men Raise Millions for Harris, Send Strong Message Against Trump

-

HUD Tackles Historic Racial Inequity In Real Estate Appraisals

-

Five Inducted Into VIAHA’s Hall of Fame

-

Unity in Diversity: Resisting the Slide Toward Dictatorship

-

Attempted Assassination: America Has Long History of Violence Against US Presidents