Civil

Black Security Guard Who Saved Democracy Fifty Years Ago, 1972

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

These days the U.S. House of Representatives is holding hearings looking into the effort to derail the 2020 election by ex-President Donald Trump who urged rioters to attack the U.S. Capitol on January

6.

Fifty years ago, a gang of Republican operatives was caught in the Watergate Complex breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington, D.C..

It led to an investigation into the episode and eventually in August 1974, Republican President Richard M. Nixon became the first U.S. president to resign.

History records Watergate as a threat to democracy, like the January 6 insurrection at the capitol, but forgotten may be the role of a man named Frank Wills who helped to save democracy at that time.

Wills was the African American security guard who uncovered and reported the break-in and set the Watergate outcome in action.

On June 17, 1972, Wills, 24, called the police after discovering that locks at the complex had been tampered with.

Five men were arrested inside the Democratic headquarters, which they had planned to bug.

When he discovered the break-in, Wills rushed up to the lobby telephone and asked for the Second Precinct police.

The police turned off the elevators and locked the doors while accompanying Wills to search the offices one by one. Five men were found in the DNC offices. Wills recalled in 1997, “When we turned the

lights on, one person, then two persons, then three The five men arrested were Bernard L. Barker, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, James W. McCord Jr., and Frank Sturgis.

One story reports that after the Watergate break-in, Wills received a raise of $2.50 per week (equivalent to $16 in 2021) above his previous $80 per week salary (equivalent to $520 in 2021). Another story states he wanted, but did not receive, a promotion for discovering the burglary.

There was brief period when he was hailed as a hero. But Wills did not receive much financial reward or a promotion and later had difficulty finding work.

He did media appearances and played himself in the 1976 film “All the President’s Men”, but spent much of his life jobless and in poverty.

Wills was born in Savannah, Georgia. His parents separated when he was a child and he was raised primarily by his mother, Margie.

After dropping out of high school in 11th grade, Wills studied heavy machine operations in Battle Creek, Michigan and earned his equivalency degree from the Job Corps. He found an assembly-line job

working for Ford in Detroit, Michigan. He later had to give up his assembly-line job due to health issues, namely asthma.

Wills then traveled to Washington, D.C. and worked at a few hotels before landing a job as a security guard at the Watergate hotel. In fact, it was considered so safe that security officers in the

building only carried around a can of mace.

According to The New York Times, Wills quit his job after the incident because he did not receive a raise. He then struggled staying employed because media

opportunities and appearances kept him away from work, most of which consisted of minimum wage jobs.

The book and film were based on Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s 1974 book accounting their investigation into the Watergate scandal.

Wills also appeared briefly on the talk show circuit.

His log entry made on June 17, 1972 at 1:47 a.m. is memorialized in the National Archives.

He shuttled between Washington and other southern cities, with some time spent in The Bahamas.

He said in an interview that Howard University feared losing their federal funding if they hired him. A security job with Georgetown University did not last long.

In the mid-1970s, Wills finally settled in North Augusta, South Carolina, to care for his aging mother, who had suffered a stroke. Together, they survived on her $450 per month Social Security checks.

In 1979, Wills was convicted of shoplifting and fined $20. Four years later, he was convicted of shoplifting a pair of sneakers from a store in Augusta, Georgia and sentenced to one year in prison.

By the time of his mother’s death in 1993, Wills was so destitute that he had to donate her body to medical research because he had no money

with which to bury her.

Only when significant anniversaries of the Watergate break-in occurred did the waning spotlight reach out towards him again. In 1992, on the 20th anniversary of the burglary of the DNC headquarters, reporters asked if he were given the chance to do it all over again, would he?

Wills replied with annoyance, “That’s like asking me if I’d rather be white than black. It was just a part of destiny.”

That same year, Wills told a Boston Globe reporter, “I put my life on the line. I went out of my way…. If it wasn’t for me, Woodward and Bernstein would not have known anything about Watergate. This wasn’t

finding a dollar under a couch somewhere.”

Wills was quoted saying, “Everybody tells me I’m some kind of hero, but I certainly don’t have any hard evidence. I did what I was hired to do but still I feel a lot of folk don’t want to give me credit, that is, a chance to move upward in my job”.

Otherwise, Wills tended his garden, made the local library his study, and led a quiet life with his cats. Frank Wills died at the Medical College of Georgia hospital in Augusta, Georgia at the age of 52 from a brain tumor.

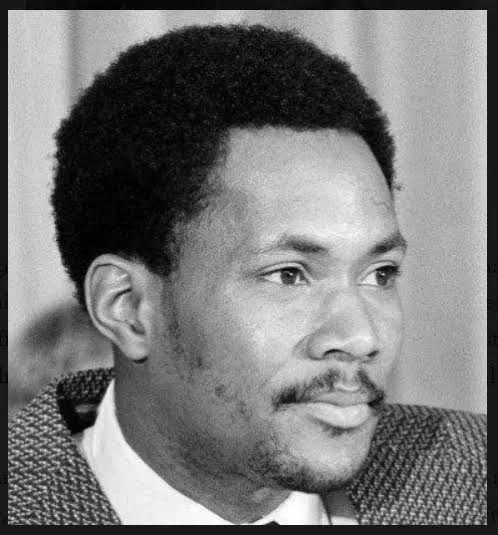

PIC

Frank Wills