Local News in Virginia

Women’s History Month: Dr. Dorothy B. Ferebee – Women’s Rights Pioneer Ahead of Her Time

“Women must feel their responsibility for promoting the physical, mental and spiritual advance of the race through study,” Dr. Dorothy B. Ferebee told congregants at a Women’s Day Observance at Norfolk’s St. John’s AME Church in 1935.

According to the Norfolk Journal and Guide which recorded her message in the paper’s May 23, 1935 edition, Dr. Ferebee continued, “The former status of women was one of helplessness in a world thought to belong to men. They had few activities and were constantly cautioned to be dependent, tearful, useless … but never strong minded. They stayed home while the boys went into a world of adventure while girls were cloistered.”

Ferebee traveled the nation to deliver speeches on civil and women’s rights. Her words and images were often featured in Black newspapers like the Norfolk Journal and Guide.

Until she died of congestive heart failure in Washington, D.C. in 1980, Dr. Ferebee, who was born in Norfolk, continued to travel and speak out on issues related to but not confined to women’s rights, civil rights and health care.

The story of Dr. Dorothy B. Ferebee is another story of a “hidden figure” of American History who contributed much to the socioeconomic, political and professional development of Black people.

Their names are not as familiar as Phyllis Wheatley, Dorothy Height, Rosa Parks or Lena Horne. Their works are often forgotten under layers of neglect by the generations after them.

These legacies are unearthed in the pages of books or the cinema, by writers and artists who want to educate current generations of their deeds.

Physician and activist Dr. Dorothy B. Ferebee is a good example. Today her name shares space with Marion Conover Hope on the front of the Ferebee-Hope Recreation Center in Washington, D.C.’s Southeast Community.

In 1925, while working with the Freedman’s Hospital (now Howard University Hospital), Ferebee, the child of elite privilege, established the Southeast Neighborhood House. It provided healthcare services for impoverished families of that section of the nation’s capital.

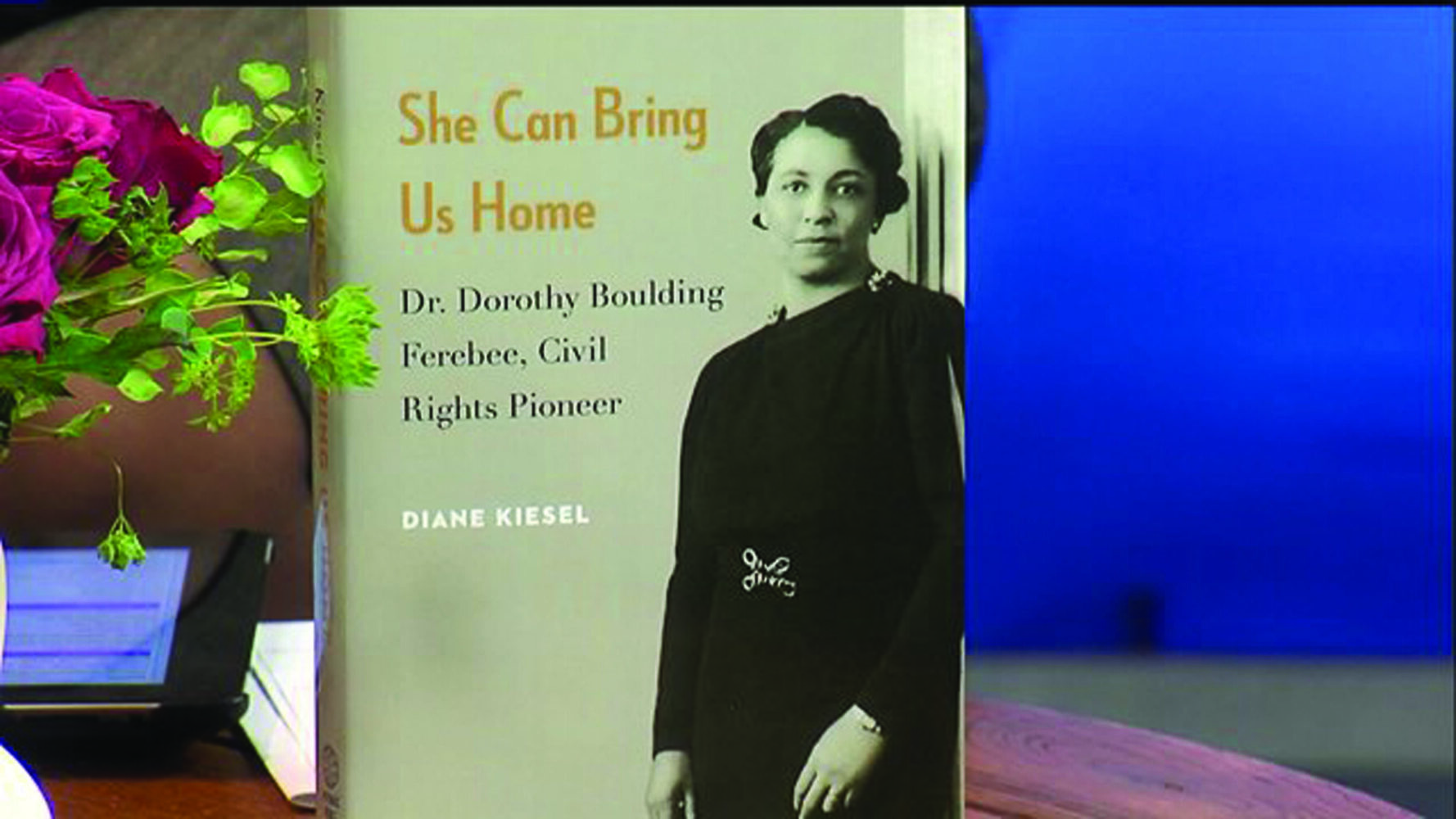

This was but one example of the works of Dr. Ferebee, detailed in a biography released in 2015, “She Can Bring Us Home: Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, Civil Rights Pioneer,” by Diane Kiesel. (Potomac Books).

The book reveals the exploits of a dynamic and busy woman from the Jim Crow 1930s until her death in 1980.

Dorothy Celeste Boulding was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1889 to Benjamin Richard Boulding, a railroad superintendent, and Florence Boulding, a teacher.

Her family moved to Boston where she and her brother Ruffin, grew up in a middle class setting in the Beacon Hill Section.

As a youth, she was exposed to a well-educated and lively group of Black professionals. They included eight men who were lawyers; one of whom was her uncle, George L. Ruffin, the first Black graduate of Harvard Law School and Massachusetts’ first Black judge.

“All I heard at the table was ‘your honor I object, or answer the question yes or no,’” her bio records. But, Ferebee said, she wanted to be a physician. As the other children played with toys, she would play “doctor”, attending to injured birds and dogs.

After graduating from English High School with highest honors, Dorothy Boulding attended Simmons College in Boston. She applied for and was accepted into Tufts University Medical School.

Despite graduating at the top of her class, she could not get an internship at any White hospital. She did acquire one at Freedman’s Hospital (now Howard University). Funded by the federal government, it was one of a few hospitals run by and providing services to African Americans.

In 1925, she joined the faculty of the Howard University Hospital, providing medical services for female students.

Later, she ran her own obstetrics practice and founded the Women’s Institute, a philanthropic group of Black women.

In 1930 Dr. Boulding married Claude Thurston Ferebee, a dentist and instructor at Howard University College of Dentistry.

In 1934, in the depths of the Depression, she left her comfortable middle class world in D.C. to travel to the Jim Crow South as Medical Director of the Mississippi Health Project, funded by the first national Black Sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha. There she and her nurses provided basic health care services for poor Black farm workers in the rural counties.

Fearing she was sent to register them to vote or preach about civil rights, Ferebee met resistance from the White farmers who often would not give the Black workers time off for medical services at a makeshift clinic.

So Ferebee asked the AKA Sorority to buy a car which she loaded with medical supplies and drove to the fields where the Black workers toiled and served them directly. The car would often get stuck on muddy roads, but she and her nurses are pictured pushing it out of the muck.

Ferebee ran what could be defined as the first form of Community Mobile healthcare services and it caught the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt, energizing Dr. Ferebee’s career and exposure.

She later became the medical director of the Howard University Health Services from 1949 to 1968. She also taught medicine at Tufts.

Dr. Ferebee was busy outside of her medical practice, namely as an AKA, serving as the sorority’s Grand Basileus, and the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW).

From 1949 to 1953, Dr. Ferebee replaced NCNW President Mary McLeod Bethune, one of her patients, as the organization’s second President. During her tenure she expanded the NCNW’s push to advocate for civil rights, better education, healthcare and other services for African Americans.

She was replaced by another able woman with Norfolk ties, Vivian Carter Mason, who was president of the NCNW until she was replaced by Dr. Dorothy Height.

Ferebee created a formidable network which included contacts with the Roosevelt and Truman White Houses, U.S. Congressmen of both parties, business leaders, and international figures.

Her progressive views stirred controversy. She supported abortion rights and her involvement with various leftist groups caused the FBI to monitor her activities and associations.

Some years afterward her death in 1980, it was reported that one of her grandsons scattered her ashes in Mt. Olive Cemetery, in Norfolk’s Berkley section, near the resting places of her parents.

After traveling thousands of miles, and devoting thousands of hours to her profession and to public service, around the United States and overseas, Dr. Dorothy B. Ferebee was finally brought home to rest.

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter