Hampton Roads Community News

WEEK TWO: Norfolk’s Community Hospital: The Rise of All-Black Hospitals Filled Void In Black Health Care

BLACK HISTORY MONTY 2022-Week Two

Norfolk’s Community Hospital: The Rise of All-Black Hospitals Filled Void In Black Health Care

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

Throughout the 400-years-plus presence of people of African descent in North America, access to healthcare has mirrored the challenges Blacks have experienced in business, education, and other areas of livelihood.

Initially, care was denied to enslaved Blacks who suffered horrific effects from the abuses of forced labor. Marginal healthcare was provided to the most valuable slaves to allow them to continue their work on plantations, while others died of disease or were worked to death.

When Blacks were treated in hospitals, it was in segregated wards, located away from Whites. The earliest recorded example of a facility serving Blacks was the Georgia Infirmary, in Savannah in 1832.

By the end of the nineteenth century, several other facilities had been founded, including Raleigh, North Carolina’s St. Agnes Hospital in 1896, and Atlanta’s MacVicar Infirmary in 1900. The motives behind their creation varied. Some White founders expressed a genuine, if paternalistic, interest in supplying health care to Black people and offering training opportunities to Black health professionals.

Untrained Black practitioners, such as midwives using the herbal and crude remedies of their ancestors provided the bulk of the care, including helping Black women give birth to their children.

During the brief period of Reconstruction, Blacks establishing institutional healthcare on their own for their own began in the form of hospitals.

Chicago’s Provident Hospital, the first Black-controlled hospital, opened in 1891. Jim Crow policies of Chicago hospitals and nursing schools provided the primary impetus for the establishment of the institution.

Others that were founded to provide care and training for Black medical professionals were Tuskegee Institute and the Nurses Training School at Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, in 1892; Provident Hospital at Baltimore, in 1894; and Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School at Philadelphia, in 1895.

According to Nathaniel Wesley, who has written extensively about Black hospitals, there were three forms of them that evolved: segregated, Black-controlled, and demographically determined.

Segregated Black hospitals included facilities established by Whites to serve Blacks exclusively, and they operated predominantly in the South. Black-controlled facilities were founded by Black physicians, fraternal organizations, and churches.

Others, as was the case with Harlem Hospital, they gradually evolved because of a rise in Black populations which led to the need for hospitals to treat the people.

Before the end of the 19th century along with Provident Hospital, there were three other hospitals operating to serve large Black communities.

Washington D.C’s Freedmen’s Hospital was established in 1862 by the Medical Division of the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide much-needed medical care to slaves, especially those freed following the aftermath

of the Civil War. The hospital was located on the grounds belonging to Howard University and was the only federally-funded health care facility for African Americans in the nation. It still exists.

Durham, North Carolina’s Lincoln Hospital was founded by Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore (1863-1923) in 1901 when he convinced Washington Duke to build it rather than a monument honoring Black slaves who fought for the Confederacy.

There was also the first edition of the Carver General Hospital in Richmond, Va., created in 1864 and closed quickly in1865.

After emancipation, Blacks joined forces to start churches, businesses, fraternal and civic groups. This included schools and hospitals they controlled and where they would be served with respect.

By 1919 approximately 118 segregated and Black-controlled hospitals existed; 75 percent of them in the South, where the most heinous forms of racial discrimination existed.

At that time, most Black health facilities were small, and ill-equipped lacking clinical training programs.

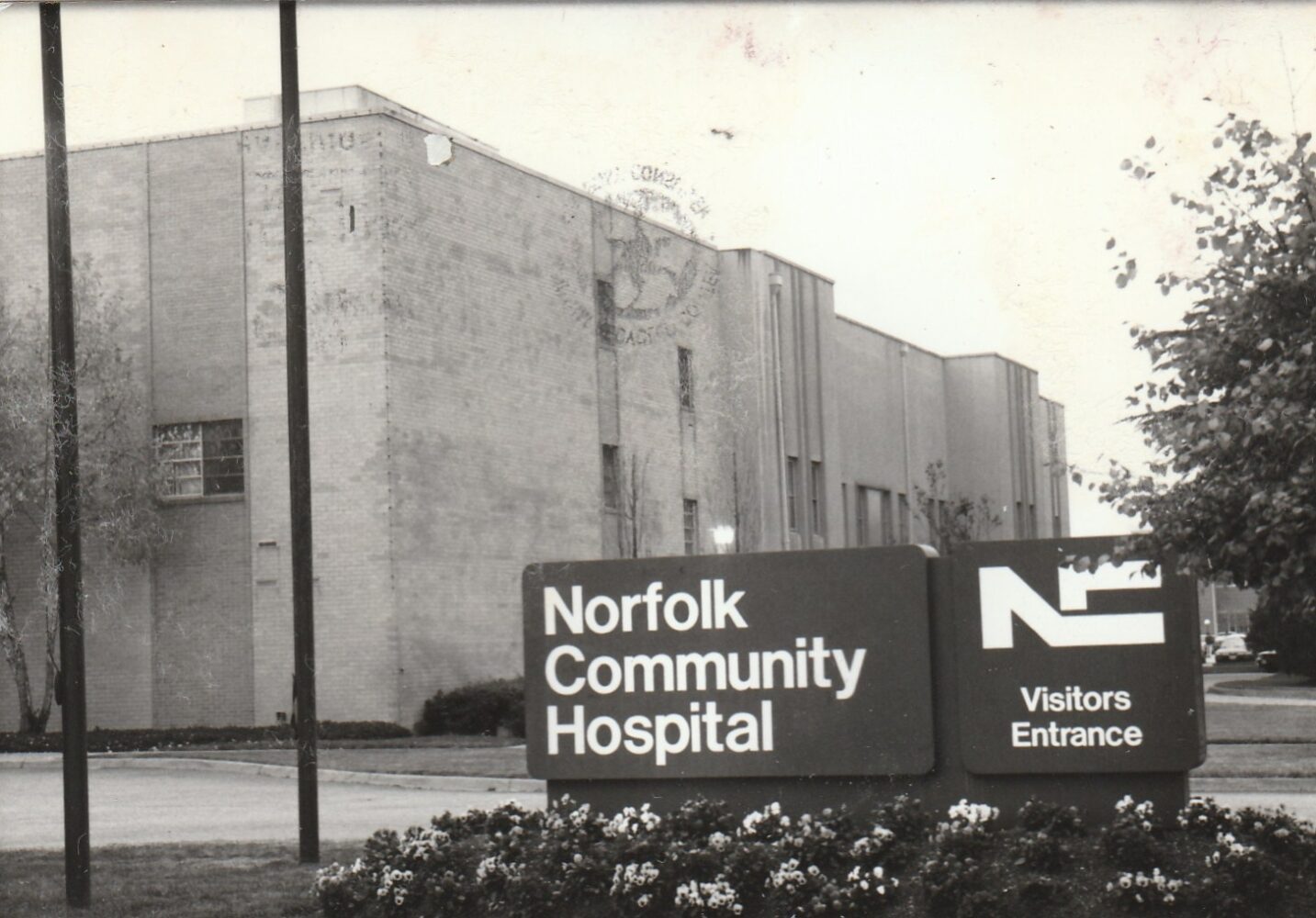

Norfolk Community Hospital Is Birthed

In Norfolk, Va., on April 16, 1915, a network of Black professionals and civic leaders came together to form the Tidewater Colored Hospital Association to establish “The Tidewater Hospital.”

Some of the key members of the group were Dr. Wilbur A. Drake, Newspaper Publisher P.B. Young, Sr., J.S. Corprew, and S. F. Coppage, among others, according to a history of the Norfolk Community Hospital (NCH), written by the late Dr. Oswald W. Hoffler, who was director of Medical Affairs of NCH in 1965.

The hospital that would grow into a major health care facility had its beginnings as a 12-bed facility located on land donated by Dr. Drake and his wife on 38th Street in the Lambert’s Point section of the city.

Along with Drake, there were five other working physicians. When Drake died in 1930, the facility was temporarily called the Drake Memorial Hospital.

In 1925, the Tidewater Colored Graduates Nurses Association established a maternity ward on Henry Street in the Lindenwood section of Norfolk. In 1932, the two facilities merged as Norfolk Community Hospital (NCH). They were moved into the quarters of the non-operative Henry A. Wise Contagious Disease Hospital on Rugby Street in Lindenwood.

That facility was a 30-bed institution with W.T. Mason, Sr., as the secretary of the Board, business manager, and administrator.

The product of the merger prospered but the space was inadequate.

The hospital received provisional approval from the American College of Surgeons in 1938 and an out-patient clinic service was begun.

Through a grant from the Work Progressive Administration (WPA), the facility expanded into a new 65-bed facility on Corprew Avenue on land once serving as a golf course for Whites only in the Brambleton section of Norfolk.

Soon after moving into this new building in November, 1939, the hospital continued to gain accreditation and enlarged its professional staff, but it was outgrowing its space.

Through the federal Lanham Act, and matching funds from the city of Norfolk, a 77-bed expansion created a 174-bed hospital, nurse’s home, power plant and garage.

Dr. Hoffler wrote that by November 1943, NCH “had all of the facilities of a modern hospital.”

This included an enlarged nursing staff, technology, and residency program to train fledgling doctors from Howard and McHenry Medical Schools.

As the 40s closed, more space for patients, storage, a new kitchen, and a new conference center were completed in 1955.

During the 1950s, patient patronage, fundraisers, and funding from the city and federal sources, all helped the facility continue its growth.

In 1957, Mrs. Fostine G. Riddick was appointed as director of nursing, the first African American in the city with an M.A. in Nursing Service Administration. Under her guidance, the nursing service flourished and it fostered the creation of nursing programs at Norfolk State and Hampton Institute.

In June, 1958 the first recovery room in the city was opened at NCH, according to Dr. Hoffler’s history of the hospital.

The continued influx of new and well trained physicians won accreditation of schools of nursing anesthesia, laboratory, and radiology technology.

Norfolk Community opened the first Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in the city of Norfolk in 1962. Unfortunately, it only operated for one year.

In 1963 to direct the nursing program at Hampton Institute, Hampton, Virginia, Mrs. Josephine D. McBride served admirably as acting director until Miss Alice Z. Welch was appointed in September 1965.

By June 1971 when Philip Brooks arrived as the Assistant Hospital administrator, the facility was a viable 210-bed, Acute Care Hospital with 410 employees including 23 physicians doctors in all of the major areas of medicine, and a $32 million operating budget.

***

A native of Charlottesville, Brooks was a resident Hospital Administrator at the University of Virginia Medical Center, one of the first.

He told the GUIDE recently, he was 25-years-old when Norfolk State University President and NCH Board Chair, Lyman Beecher Brooks personally recruited him to Norfolk and NCH.

By October of that same year, Phillip Brooks was named Chief Administrator of “what I saw was best Black-operated medical facilities in the nation,” he said.

“It served as a source of leadership and service to the community,” he said. “It served as a model for hospitals all over the country so far as training and administration.”

But Brooks and other medical professionals working at NCH began to see that there were forces that would cause the demise of it and other Black-owned hospitals across the nation.

To Be Continued…

You may like

Virginia House Speaker To Keynote NSU’S 112th Commencement

Disbanding of TSU’s Board of Trustees: An “Attack On DEI”

THE PATH OF TOTALITY: If You Missed It, Catch Next One In 20 Years!

Black Family Scholar, Pioneer: HU Presents Lifetime Award To Dr. Andrew Billingsley

Hampton Roads Delivers Another Successful UNCF Mayors’ Masked Ball

Baltimore Bridge: A City’s Heartbreak, A Nation’s Alarm