Black Arts and Culture

WEEK THREE: Black Hospital Provided Quality Medical Care For Community

BLACK HISTORY MONTY 2022-Week Three

Black Hospital Provided Quality Medical Care For Community

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

Looking back at his eight decades of life, Dr. John Hopkins, at various stages, has found himself among a unique few in his professional class.

The Trenton, New Jersey native, after graduating from HBCU McHerry Medical School, was among a few Black medical students at Ohio State University. He recalled walking alone through the halls “in a long white coat” as a medical resident of Radiology at Vanderbilt University.

Once he secured his credentials to practice, he recalled that the first convention in 1963 of 13 Black Radiologists in Chicago could be held in one room.

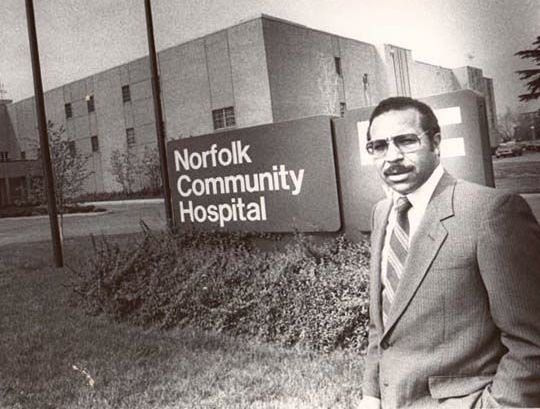

After a brief period of teaching and practicing at McHerry, with a wife and three children in tow, he landed a job at Norfolk Community Hospital (NCH) in 1975.

Forty-seven years later, he is among a shrinking group of the medical professionals who worked at the hospital during its heyday.

Thousands of Norfolk residents proudly claim they experienced their first moments of life in the Hospital’s maternity ward.

There are several physicians, specialists like Hopkins, and nurses who retired from the hospital who are still in the area. And, there are nurses still working in their fields after years of serving at NCH which closed its doors in 1998.

When Hopkins arrived, he said NCH was at a crossroads. From its inception in 1915 as a 12-bed facility built to provide care and dignity to Black residents to a 210-bed acute care facility with over 400 employees before it closed.

In 1975, NCH dedicated its last expansion, a 15,000 square foot addition that housed the beds and service area for the Radiology Department.

“At that time I recall Dr. (Oswald) Hoffler, who was the Medical Director, who oversaw the operations, which was a model,” said Dr. Hopkins, who still lives in Norfolk.

“I was the only Black Radiologist at the hospital and in the city at the time,” he said during an interview with the GUIDE recently.

Twenty-three physicians were certified and respected in every field of general and specialized medicine. Norfolk Community was just as good as many White hospitals in the area.”

Dr. Hopkins recalled many of NCH’s staff physicians had their practices serving the community. He said the nursing staff was well trained “and dedicated” to the patients.

“We were a highly regarded as a teaching hospital, one of the few Black ones in the nation.”

“All of the physicians were dedicated to staying updated on the latest techniques and technology,” said Dr. Hopkins. “I don’t think any of the non-Black hospitals had the kind of training program Community ran. We were unique. We had training sessions constantly. We also had a steady flow of interns and residents from the Howard, McHerry, and White medical schools.

“They were impressed with their training,” he said. “They connected with the community and many stayed here to practice medicine and start families.”

The hospital was the largest employer of Black professional medical and support staff in the South, where most Blacks and the hospitals which served them existed.

Four years before Hopkins arrived, 26-year-old Phillip Brooks was hired as the Assistant Chief Administrator of NCH in April 1971. He was the lone Black member of the 1971 UVA Health Care Administrator (HCA) class.

In October of that year, he was named the Youngest Chief Administrator of an Acute Care Hospital in Virginia.

Along with Dr. Oswald Hoffler, who was a noted surgeon, there was Dr. James Willie, a noted Obstetrician, and the NCH Professional Association, Inc., a group of Black physicians and dentists.

The 11-member plus group was a source of professional mentorship and cooperation. A good example is the construction of the Professional Medical Building at 549 Brambleton Ave in 1965. It still stands and houses the JenCare Medical Services group.

Dr. B. J. Tucker and elements of that group, orchestrated the development of a five-story medical and professional building around the corner in the 500 block of Church Street. It has been demolished.

Phillips Brooks said NCH built the first two community health clinics in the region. One was located in Suffolk; the other was located in the Braywood neighborhood on Johnstons Road near Bank Street Baptist Church.

“Community was a source of healthcare and leadership,” said Brooks.

Dr. Hopkins said this kind of cooperation and “brotherhood” among Black physicians locally no longer exists. Instead newer generations of Black physicians are staff members of corporate medical entities.

Dr. Hopkins and Brooks recall NCH’s role when Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS) was being formed.

“The idea to form a medical school had broad regional support,” said Hopkins. “The initial organizers were very liberal-minded. They did not want the White good ole boy system to dictate how it was developed and wanted Community Hospital to have a role.”

Hopkins said that one of the first African American Board members of EVMS was NSU faculty member Dr. Yvonne Miller, who was recommended by

Dr. Lyman B. Brooks, Norfolk State University’s (NSU) President and chair of NCH’s board who had a hand in forming EVMS.

Dr. Miller would later become the first Black female State Delegate and Senator.

Dr. Hopkins said he replaced Dr. Miller on the EVMS Board. He was the first “practicing” Black medical professional appointed to that panel.

Apart from federal, local public funding, Brooks said NCH relied on its Axillary, civic and fraternal organizations which organized fundraisers, and on donations from philanthropists who provided thousands

of dollars to NCH to operate.

Both Brooks and Dr. Hopkins recall the level of work and dedication Dr. Lyman B. Brooks devoted to NCH.

There was a close association between NSU and NCH, said Hopkins. NCH helped build the nursing programs at NSU and Hampton University.

“I don’t know how Dr. Brooks did it…or whom he knew… but he could go out into the community, access funding and other resources for that hospital,” he said. “He had a pristine reputation and no dirty sleeves. He helped build relationships with other hospitals and

institutions. He also knew how to recognize talented people.”

They are not related, but Dr. Brooks recruited and hired Phillip Brooks, who was the lone Black member of the 1971 UVA Healthcare Administrator class.

The Demise of NCH and Other Black-Controlled Hospitals

By 1990, various factors were taking their toll on NCH and other Black hospitals. In 1919 there were 120 of them up until the late 1940s.

By 1990, there were only eight, according to Nathaniel Wesley, who has written extensively on the history of Black hospitals.

Along with NCH, two existed in Virginia: Whitaker Hospital in Newport News and Richmond’s Community Hospital.

One of the key factors was desegregation which expanded options for employment and higher pay for medical professionals and Black patients were no longer relegated to the “colored” wards in the basement.

“We would recruit highly trained physicians to Community,” said Hopkins. “But a White hospital that could pay more would lure them away.

Another key factor was financial. During the mid-1990s, according to Brooks, the federal government changed the way it funded community

hospitals. Brooks said this “accelerated the closure” of Black hospitals serving large urban and rural communities.

Even efforts to secure funding via the Virginia General Assembly were turned back.

“Finances were always a challenge for Black hospitals,” said Hopkins.

Despite efforts to secure funding and donations, keeping up with technology required money and that was a challenge as well.”

Losing accreditations, due to a lack of certified personnel and medical resources weakened NCH’s standing, as well.

Phillips Brooks and the Board by the mid-1990s were in a constant battle with various accreditation agencies which revoked the credentials of the NCH.

Brooks said he was forced to reduce staff, curtail its emergency room and other services by the mid-1990s.

By mid-1998, NCH could no longer operate as an Acute Care facility and had to close its doors.

But Brooks with long-time supporters worked to keep the doors open. At one point the old facility was converted to a community clinic, housing the practices of several Black physicians who were on the NCH staff in the past.

Brooks and members of the community sought to raise money to rehabilitate the aging building. It was a futile effort.

In the early 2000s, as a part of the old building was being torn down, several ideas about how to use the remainder were floated, but were sunk, by the lack of funds and community interest.

NSU eventually bought and razed what was left.

Now NSU’s public safety building sits where Norfolk Community Hospital once stood. There is an effort to erect a historic marker to remind people of its location.

Today Howard University Hospital is the only historically Black Acute Care facility still operating.

“When I drive by there, it hits me…and I recall the importance of what once stood there,” said Brooks, who now manages a community health care facility in the Huntersville section of Norfolk.

“I think about the good work we did out in the community. It was a good example of what the Black community can achieve. I hope that marker is not the last of that legacy.”

“It was truly a community organization,” said Dr. Hopkins. “It was the Black community that sacrificed and built it so we could be treated with dignity when we were sick or had an opportunity to be trained to serve them.

“But more so, it was community, not because of the doctors or nurses only,” he continued. “It was the people who came in on a cold morning to man the kitchen or clean the halls, or office workers who greeted the people. People who could afford to go elsewhere came in and supported that hospital. What about the staff who was never late?

“They never complained even though their pay was late or they never got a raise. They were proud of that hospital which provided them with not only employment, but dignity when other places did not.”