National Commentary

The Road To Voting Rights Was Rough

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal & Guide

On November 4 the nation will conduct its 57th presidential election. The electorate will either replace or retain the 45th President of the United States.

There will also be electoral contests between the two main political parties to determine races for U.S. Congress, state and local political offices.

This pivotal election is being held in a year when the theme for Black History Month resonates: “2020-African-Americans and the Vote.”

Throughout February, forums will be held and oratory will be delivered to mark the importance of the right to vote.

Today the right and ability of most Americans to vote are theoretically unencumbered by race, income or gender.

But the right to participate in the nation’s political system was not always that free, especially for African-Americans, women and other people of color.

The original United States Constitution (1787) mostly left the issue of voting rights and regulations up to the states.

With a few exceptions of several states in early America, only property-owning white men could vote, be elected to political office or even serve on juries.

As the country expanded, so did the number of eligible voters.

In the early 19th century, most property qualifications for voting and holding elected office positions were removed.

President Andrew Jackson, while forcefully removing large numbers of native Americans from their land on the East Coast, helped white men who did not own land to vote.

But Black Americans, who were still slaves and not officially citizens, were barred from voting and participating in the political process.

The first U.S. women’s rights movement was closely allied with the antislavery movement, and before the Civil War, Black and white abolitionists and suffragists created a coalition.

During the antebellum period, a small coalition of formerly enslaved and free Black women, including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Maria W. Stewart, Henrietta Purvis, Harriet Forten Purvis, Sarah Remond, and Mary Ann Shadd Cary, were active in women’s rights circles.

They were joined in their advocacy of women’s rights and suffrage by prominent Black men, including Frederick Douglass, Charles Lenox Remond, and Robert Purvis, and worked in collaboration with white abolitionists and women’s rights activists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony.

In 1848, the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York.

Black women abolitionists and suffragists attended, spoke, and assumed leadership positions at multiple women’s rights gatherings throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

In 1851, former slave Sojourner Truth delivered her famous “Ain’t I A Woman” speech at the national women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio. Sarah Remond and her brother Charles won wide acclaim for their pro-women suffrage speeches at the 1858 National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City.

But due to the Civil War, Black men would gain the voting franchise first, and this created a rift between African-Americans and white females seeking the vote too.

By 1860, only five states – Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont – allowed African-American men to vote without significant restrictions.

But, even as the right to vote expanded for white males, new laws made it increasingly difficult for African-Americans to vote.

African-American men lost the right to vote in states like New Jersey, Maryland and Connecticut where free Black men could vote in the early years of independence.

Unfortunately, leaving election control to individual states led to unfair voting practices in the U.S.

Blacks especially were prohibited from voting and other rights bestowed on whites by the Constitution, due to the imposition of “Black Codes,” not only in Dixie but parts of the North.

President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves only in the Confederacy, in 1863 during the Civil War.

Bolstering their claims to freedom, Black men joined the fight for their freedom to abolish slavery and reunite the union.

By enlistment and voluntarily, 179,000 Black men (10 percent of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 Black soldiers died over the course of the war – 30,000 of infection or disease.

This occurred while millions of their brethren were still in bondage.

This willingness by Black men inspired the Republican-controlled Congress to amend the constitution to provide a path to civil rights and voting rights.

♦♦♦♦

Three critical changes to the Constitution are known as the Post Civil War Reconstruction Amendments.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the U.S. and its territories.

Since at the time Black people were not granted citizenship, it was improper to refer to the 3.5 million people of African descent as African-Americans. But the 14th Amendment changed that and declared that everyone born in the U.S. is a natural citizen. Adopted in July 9, 1868, it also granted Blacks due process under law, the right to hold public office, suffrage, compensation for emancipation and debts of war.

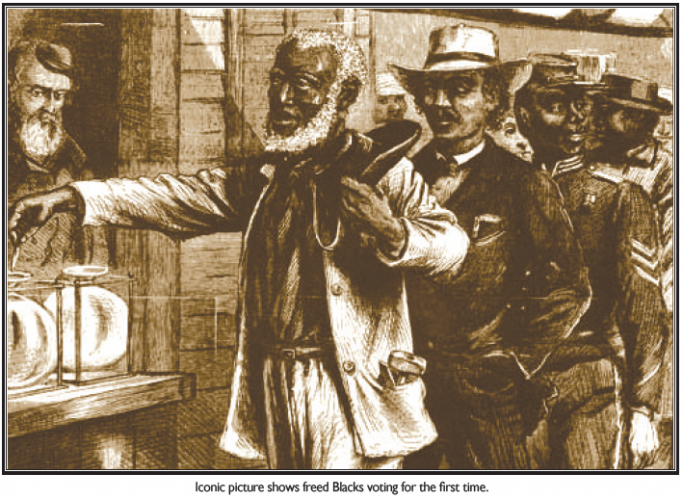

Five years after the Civil War, the 15th Amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870, it granted African-American men the right to vote.

This legislative victory was applauded by abolitionists and the Black community.

Armed with the right to vote, many African-American men joined forces with the Republican Party.

Various historical accounts, such as the Martin Luther King Commission of Virginia, which recorded the Reconstruction advances of Blacks in Virginia, said many Black men who had fled the state returned to take advantage of the new political freedoms.

They also forged alliances with the Republican party to participate in the political process in the South, notably. The alliance fostered local and state elections which took control of all southern state governorships and state legislatures, except for Virginia, initially.

Many southern states had to hold conventions in the South to amend their constitutions, to reenter the union, and to expand civil and voting rights for Blacks.

African-Americans attended those gatherings, and many were intellectually prepared and participated, contrary to some historical accounts years afterward to weaken Reconstruction.

Twenty Black men attended the one in Virginia in 1867-1868. One of their major goals was to secure the right to vote and other civil rights protections.

Many of these delegates and future Black officeholders were Black men who escaped north to avoid slavery, former ones fresh from bondage or free Black men who lived in the South, before and during the War.

Using the newly created bloc of Black male voters, the Black delegates were elected to local, state and federal officials.

At the beginning of 1867, no African-American in the South held political office, but within three or four years about 15 percent of the officeholders in the South were Black – a larger proportion than in 1990.

Most of those offices were at the local level.

In 1860 Blacks constituted the majority of the population in Mississippi and South Carolina, 47 percent in Louisiana, 45 percent in Alabama, and 44 percent in Georgia and Florida, so their political influence was still far less than their percentage of the population.

The Black delegates helped their white allies write laws which provided for educational and social change, including the first policies to create public education.

You may like

Disbanding of TSU’s Board of Trustees: An “Attack On DEI”

GOP Voter Fraud Push Is Attempt To Disenfranchise Black and Hispanic Voters

Voting Rights Act Threatened –Again!

“We March On”: Not A Commemoration, But A Continuation

Voter Suppression In Chesapeake? 2 Early Sites Closed

Sixty Years Later, Marchers Plan Return To Washington, Aug. 26