Black Arts and Culture

Resisting Oppression Through The Courts

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of happiness.”

Thomas Jefferson, in the lead sentence of the Declaration of American Colonists’ call for “Freedom and Independence” from Britain, appropriated these words from English philosopher John Locke.

The rebel colonist adopted a Bill of Rights to a Constitution, which included the freedom to assemble, bear arms and due process, own property, and a trial by peers.

But nearly half a million enslaved and free Black Africans who lived among the 1.6 million whites counted in the 1770 Census ran into a wall that deterred them from such privileges.

Initially, Blacks resisted this exclusion by using various legal cracks in it.

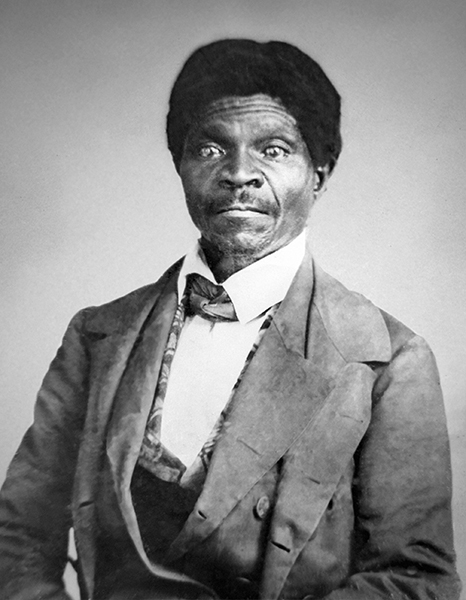

The famous Dred Scott decision is highlighted as an example of Blacks in America using the courts to resist oppression.

Scott accompanied his master from Missouri, a slave state, to Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal.

When his owner later brought him back to Missouri, Scott sued for his freedom. He claimed he was taken into “free” U.S. territory and was automatically freed.

Scott sued first in Missouri state court, which ruled that he was still a slave under its law. He then sued in the U.S. federal court, which ruled against him by deciding that it had to apply Missouri law to the case. He then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court in March 1857 issued the 7-2 decision that people of African descent had no rights a white man had to respect because they were not citizens.

According to an article written by Abigail Higgins in March of 2021, the words from 1780 that “all men are born free and equal,” echoed in the small town of Sheffield, Massachusetts. The line was from the state’s newly ratified constitution.

There, Elizabeth Freeman, known as “Bett,” a slave, understood the irony as she watched the white men around her declare freedom and she wanted the same 80 years before Scott.

Freeman marched, by some accounts, to the house of Theodore Sedgwick, a lawyer, and demanded he represent her in her case to secure it.

Sedgwick agreed to represent her in what was called “the trial of the century,” which would rock the entire institution of slavery.

“She was kind of the Rosa Parks of her time,” says David Levinson, author along with Emilie Piper of “One Minute a Free Woman,” a book about Freeman.

Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery.

But state law recognized slaves as property not persons. So, they could prosecute the men who owned them, to prove lawful ownership.

By 1780, nearly 30 enslaved people had sued for their freedom based on a variety of technicalities, such as a reneged promise of freedom or an illegal purchase.

Freeman did not seek her freedom through a loophole but through her will to resist and abolish the practice of slavery.

Freeman was well-known, respected, traveled widely, and engaged white people which was unusual for an enslaved Black.

Though Freeman could not read or write and there was an ‘X’ mark on a deed for her home, Levinson called her “the perfect person to be the plaintiff. If anyone should be free it should be her.”

Attorney Sedgwick himself owned slaves. Boston was a hub of abolitionist organizing.

A jury of twelve local farmers, all white men according to Levinson, ruled in favor of Freeman in 1781, giving her freedom and 30 shillings in damages.

The first thing she did was cast off her slave name in favor of one that celebrated her new status.

But even before Freeman, there was Quock Walker in Massachusetts.

Walker was inherited by Nathaniel Jennison from his owner James Caldwell, who died. He promised Walker freedom when he turned 25 and he was already 28. He fled, was caught and Jennison beat him.

Walker sued him for assault and battery, claiming Jennison did not own him. He won and Jennison was forced to pay him damages.

Walker’s case, along with Freeman, was the death knell for slavery in Massachusetts by 1790.

***

After the Civil War, the 13th amendment of the Constitution ended slavery; the 14th granted them citizenship and equal protection and the 15th gave Black men the right to vote.

These Amendments also provided stronger legal weapons to protect Blacks from continued marginalization.

In 1892 Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man boarded a “whites-only” train car in New Orleans. He violated Louisiana’s Separate Car Act of 1890, requiring “equal, but separate” railroad accommodations for Black and white passengers.

Plessy was charged but he claimed the case should be dismissed because of its unconstitutionality under the Equal Protection clause of the 14th amendment.

The request was denied by Judge Howard Ferguson and the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld his ruling.

Plessy appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson case. In the landmark 7-1 decision in May 1896, the high court said segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities were “separate but equal.”

That decision legitimized the Jim Crow segregation laws imposed in the South and North after the Reconstruction era on African-Americans educationally, economically, socially, and politically.

None of the instances were “equal” in public accommodations, schools, housing, or economic access.

As an act of resistance, African-Americans created their own educational and socioeconomic institutions.

Black business districts provided goods and services. Black doctors, lawyers and merchants, and other professionals established a service class.

They were trained in Black high schools or colleges created by Black communities or white in the North if they were willing to serve Blacks.

Black professionals lived next to the factory worker and maids, for both blue and white-collar families were denied access to white enclaves.

***

But Black lawyers fueled by the advocacy of organizations such as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), chipped away and resisted institutionalized Jim Crow.

The case that broke the back of Jim Crow’s “separate, but equal,” culture and changed America, according to historians, centered around segregated schools.

Brown v. Board of Education was the brainchild of some of the nation’s best African-American attorneys: Robert Carter, Jack Greenberg, Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley, Spottswood Robinson (Virginia), Oliver Hill (Virginia), Louis Redding, Charles and John Scott, Harold R. Boulware, James Nabrit, and George E.C. Hayes.

Thurgood Marshall was the leading architect of the strategy that ended state-sponsored segregation. Marshall founded LDF in 1940 and served as its first Director-Counsel.

Marshall was the attorney in other cases before Brown, including the pay equity case in Norfolk, filed in 1935.

The Norfolk Teachers Association and the Virginia State Teachers Association joined the NAACP to challenge the pay disparity between Black and white teachers as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution.

Eilene Black was the first plaintiff in the lawsuit.

Black and other teachers at Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk had earned higher degrees than many white teachers.

Yet, they received a minimum yearly salary of $699 and a maximum of $1,105; white high school teachers received a minimum of $970 and a maximum of $1,900.

Black’s case was dismissed. But the lawyers led by Marshall, with another Plaintiff Melvin O. Alston, eventually won.

Years later, when Marshall and his legal team fought to desegregate the public schools, they combined five associated cases including Brown vs. Topeka, Kansas to argue and win before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954.

One of them was Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia.

When southern states, including Virginia, engaged in “Massive Resistance” to dodge compliance, Marshall and NAACP lawyers continued to challenge the “resistance.”

On February 2, 1959, the nation witnessed 21 Black students entering previously all-white schools. Seventeen of them entered six previously all-white schools in Norfolk which had been closed in defiance after the courts ordered Norfolk to admit them in the fall of 1958.

Ironically, a group of white parents in Norfolk filed a case to reopen the schools using the 14th Amendment claiming their children were being denied equal access to education.

Compliance with Brown did not fully take place until the late 1960s into the 70s.

To this day, the legacy of Black resistance through legal channels to socio-economic racism continues, despite the perception of progress in this nation.

One present day example of Black resistance against racial injustice using the legal system involves the number of civil lawsuits filed by families where unarmed Black men and women were killed in conflicts with police or civilians. A few of the more well-known cases include Trayvon Martin of Florida, Eric Gardner of New York, and George Floyd of Minnesota.