Hampton Roads Community News

Portsmouth Police Chief ouster arouses ire from community

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

“I can assure you that I did not quit on the citizens of Portsmouth,” Tonya Chapman said in a letter she released to the media on Monday, March 25, one week after suddenly resigning from her nearly three years as Portsmouth’s Top Cop.

Chapman continued, “As such my resignation was not tendered under my own volitions. This was a forced resignation and our City Manager was the conduit.”

That statement from Chapman along with Chapman’s charge that the Portsmouth Police Department is biased have raised the ire of the Portsmouth community about why the city’s first African American woman police chief was suddenly released from her position by City Manager Dr. L. Pettis Patton.

On Tuesday night, March 26, about 200 people, including a cadre of members of the Portsmouth Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., attended the Portsmouth City Council meeting to voice their concerns. Among those who spoke about the issue were State Sen. Louise Lucas, a former Portsmouth City Council member, who praised Chapman and criticized Patton’s action. Lucas also is calling for a state and federal investigation of the ouster. (See summary of Lucas’ statement inside on page 2.)

Resistance from an entrenched and racist cadre of police officers who resented her efforts to diversify the department played a significant role in Chapman’s being forced to resign as Portsmouth’s Police Chief, according to Chapman’s letter.

But Chapman noted that the most “heart wrenching” and surprising part of the scenario related to her exodus were the actions of City Manager Dr. L. Pettis Patton, with whom she had established a very professional and warm relationship.

She said prior to her recent vacation, she and the City Manager had a very warm exchange.

While on vacation, she received a message from the City Manager requesting that Chapman meet with her upon returning home. The former chief said she then sought to contact Patton, to no avail, which she found usual.

Chapman said when she met with City Manager Patton, “she began to read a scripted document that stated in part I had lost the confidence of my department.”

Chapman said she asked the City Manager for specifics on why it had occurred and noted the attempted vote of “no confidence” from members of her department.

“She then continued reading and then asked for my resignation,” said Chapman in her letter.

Chapman said she continued to insist on additional information but was given nothing else.

Chapman said she had not been counseled or warned on any issues.

“She then stated that if I did not sign the pre-written letter of resignation, she would terminate me,” said Chapman, who said she could not believe the action was taking place.

“She then stated that if I signed the letter that I would receive two months severance pay through May 17, 2019,” Chapman said. “After signing the letter under duress, she then stated that was effective immediately. I ask you if I had done anything wrong to warrant my

immediate dismissal, would I have been offered severance?”

On the evening of the letter’s release at 6 p.m., the Portsmouth NAACP, members of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives and irate residents stood in front of the Confederate monument in downtown Portsmouth to show support for Chapman and denounce how she was treated.

James Boyd, the President of the Portsmouth Chapter of the NAACP, said the staging of this event at the foot of the Confederate monument symbolized the racist nature of the city’s political tension now.

In her three-page letter, Chapman outlined what she said were the factors which led to her surprise exodus on March 18 as the first African American female police chief of a major Virginia city which is majority Black.

Chapman released the letter a week after she stood next to the City Manager of Portsmouth Dr. L. Pettis Patton and announced her resignation, with neither one of them giving a definitive reason.

Questions for why Chapman resigned with no explanation, had been asked by the public and the media since March 18, with various scenarios produced.

But in her letter, Chapman provided some specific examples of the antagonists who were key players in events leading up to her exodus.

She noted that the crux of her resistance was the indigenous racial climate and tension with members of the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) which is mostly white.

Also, Chapman said in her letter that apart from officers under her command, “I would contend that there were some politically connected individuals that never had confidence in me in the first place.”

She mentioned that the resistance to her command were fostered by the FOP members who were disciplined for violations of policy. She also suggested this resistance was powered by the inability of the group’s mostly white and male membership to accept commands from a Black female.

She said the organization had “tried to generate a vote of no confidence on me for the past two-plus years without success as they have not been able to articulate valid reasons” for doing so.

“Furthermore, I have been advised by reliable sources within the department that the only other chief they have generated a vote of “no confidence” on was a former Black male chief,” she wrote in her letter. “In fact, I was told that a former white male chief came in and turned this department upside down to including dismantling units and transferring personnel due to various allegations and they did not even attempt a vote of ‘no confidence’ on him.”

In her three-page letter, Chapman delivered a timeline which reflected the most positive aspect of her 2.5-year tenure and the most disturbing.

“Unfortunately I cannot provide additional information on the reason for my sudden departure,” Chapman wrote. “However, based on experiences I have endured over the past few years, I can certainly conjecture and so can you.”

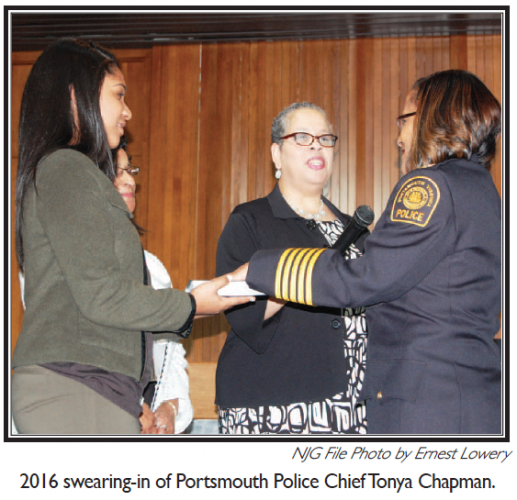

Chapman opened her letter describing the excitement in the community and the pride “in the eyes of family members, coworkers, friends, and state officials” created by her being named the first Black female police chief in Hampton Roads.

Chapman said she noted in her swearing-in speech that “I had been advised numerous times that I had a difficult task ahead of me. I was then assured that I was up for the challenge.”

Chapman said she had also been advised “of the external strife that existed between the community and the police department as a result of several officers involved in shootings and I was also aware of the public frictions between city leaders.”

Chapman said despite the caveats, she was not deterred from assuming her new job and role.

Prior to her arrival, a year before, Stephen

Rankin, a white policeman, shot and killed 18-year-old William Chapman II.

The incident took place outside a Walmart when the 18-year-old Chapman was accused of shoplifting. The officer claimed that Chapman, when confronted, had knocked away the officer’s stun gun and then charged at him causing him to kill him.

A circuit court jury found Rankin guilty for the killing of William Chapman in April 2016. It was the second time Rankin had killed an unarmed man while on duty. He now faces up to 10 years in prison.

“…..(T)he internal strife included racial tension within the police department (that) became blatantly apparent to me,” upon her arrival to assume command of the department, Chapman said.

She continued, “Having been a member of two other law enforcement agencies I have never witnessed the degree of bias and acts of systematic racism, discriminatory practices and abuse of authority in all of my almost 30-year career in law enforcement and public safety.”

She said she was determined to change the culture.

She said that “some of the incidents are so inflammatory, I am reluctant to make this publicly available out of concern for public safety; however, I am willing to share specific information with the appropriate governmental entity.”

But she said that only a “small contingency of the Portsmouth Police Department were involved in such activity and the rest were able to serve the community with respect and dignity.”

In her effort to undercut the racist elements of the department, Chapman said, “I was often met with continued resistance from some members….”

“An effort was made to create transparency, accountability and have members of the department embrace principles of 21st Century Policing,” she said in her letter. “My goal was to develop a highly ethical, high performing organization that embraces diversity and treats everyone with respect and dignity.”

“I am elated to report that most officers embraced that same spirit.

Chapman said there were a few that were resistant “to change which was expected as legitimate change is always difficult.”

She noted that officers who resisted her efforts were dealt with various disciplinary policies and “we experienced a lot of success.”

Chapman said that within the first four months of her tenure, she implemented geographic policing with an emphasis on officer and supervisor accountability, consistency…along with building community trust and goodwill.”

The result was a 52 percent reduction in homicides during her first year of 2016; reduction of crime by 7 percent in 2017 and an 8 percent in overall major crimes. Women and minority representation increased from 36 to 46 percent within two years; minority presence increased to 31. The department recruited over 50 recruits within one year, which consisted of 74 percent women and minorities in 2018.

Chapman launched other “community policing efforts including “walk and talk, teens and traffic stop program, faith behind the badge coalitions and the Rapid Engagements of Support in the Event of Trauma of RESET walks.

“This was a ‘constructive firing’ (of Chapman),” Portsmouth NAACP President James Boyd told the GUIDE. “All signs lead to termination. She could not clear out her desk… ultimately under duress. It seems that the City Manager had pressure from the city’s political leadership and the racist elements in the city’s Police Department.”

“(Patton) may not have been the conduit, but she was the electricity which generated it,” said Boyd. “She was the vehicle. This is the same system which sought to get rid of (former council member) Dr. Mark Whitaker and the former Black City Auditor who was forced out of office.”

Former Council Member Whitaker, who still knows the inner working of the city council’s machinery, said that “Patton acted on the blessing of the city council, who I am sure was influenced by the members of the police union. There was nothing Chief Chapman did wrong.”

“One of the union members disciplined by Chapman was one of its top leaders,” said Whitaker. “He called a Black officer a trunk monkey and that is well known. Dr. Patton is highly regarded among city officials and she would not have done this unilaterally. She should have shown more moral leadership.”

Whitaker said that he sought to address many of the issues that Chapman was working on when he was on council.