Local News in Virginia

Part Two: Remembering Black History As Naval Base Turns 100

Throughout 2017, the U.S. Navy is observing the centennial anniversary of the opening and dedication of the Norfolk Naval Base/Station.

In the coming weeks, the New Journal and Guide will be presenting a series of articles detailing told and untold stories related to the African-American experience at the sprawling complex.

Most of the articles in the GUIDE archives are positive, revealing military and civilian African-American personnel who were honored for their work and dedication to the service; many were the “first” of their race to accomplish various feats.

But the GUIDE did not shy away from detailing less flattering portions of the naval base’s history, such as the fights by African-American military and civilian personnel against demeaning racial discrimination.

♦♦♦

Before women were admitted into the ranks of the Navy, only Black men could enlist or were drafted into the service.

Until World War II, they were restricted to careers as messmen and stewards, trained to cook, clean and maintain the living quarters of enlisted and officer personnel who were White.

In an October 30, 1937 edition of the GUIDE, during the early stages of WWII as the German War Machine was gearing up for action, a headline read, “40 Mess Attendants Finished Training Naval Base Norfolk.”

“More than forty young Black men will leave the Naval Operating Base here on Friday for a 15-day leave of absence. These men have completed the training requirements in the mess attendant class, having spent three months under the direction of Joseph Thompson, first class steward.”

Thompson was to begin another class the following December. He had 18 years in the service training African-American stewards.

The trainees hailed mostly from Dixie, the majority from South Carolina, Virginia and as far away as Arkansas and Texas. After their 15-day leave, they would be assigned to various shore bases and naval vessels throughout the fleet.

Gradually the first appearance of Black male sailors in roles other than as messmen and stewards began during and after WWII. Also, the first Black officers were assigned to mostly supply side roles on the base.

On and off the base, before President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order in 1948 to desegregate the U.S. military, including the Navy, racial tensions and violence between Black and White sailors were high.

This was especially true when on-base enlisted clubs were desegregated. Also just outside the gates of the base along the northern stretch of Hampton Boulevard, stories of fights between Black and White enlisted naval personnel were common.

In fact, at one point, during the early 1950s, White business owners near the front gate of the base proposed barring Black servicemen from their businesses, fearing fights and other disruptions.

White businessmen reportedly even plotted to hire White women to engage Black men and falsely accuse them of heinous sexual crimes to deter them from frequenting the bars and other businesses along the strip, according to reports by the GUIDE and the city’s NAACP, In an April 24, 1971 edition, the GUIDE reported on a letter sent to the Chief of Naval Operations, Congressman G. William Whithurst, NAACP, SCLC, and the Naval Base Commander, from a well known bar owner outside Gate 2 named “Flip Flop Stevens,” who complained about the efforts of his fellow White bar owners to keep the Black sailors from patronizing their bars.

♦♦♦

In the October 16, 1954 edition of the GUIDE, a headline read “Naval Base Blacksmith Retires; Ends 33 Years.

“W.W. Sledge a … Blacksmith in the Norfolk Naval Supply Center’s Material Services and Maintenance Department and one of the Center’s most inventive employees retired last month because of ill health.”

According to the article, Sledge received one of the Navy’s highest civilian honors: the Meritorious Civilian Service Award.

“He is most widely known for his power ram and more than 100 dyed and backing plates which he designed and fabricated. For saving the Navy an estimated $20,000 in one year, with the ram, he won a beneficial suggestion award of $275 in 1951.”

“Two years later, because of additional savings at the Center, he won another award of $50 and commendations from the Assistant Secretary of Navy for Air.”

Sledge came to the base as a laborer three years after it opened, the article said.

In 1939, he was promoted to helper general and in 1941 to auto mechanic. Largely self-taught, he was known as one of the best auto mechanics at the center.

“In 1944, he was promoted to Blacksmith. He was given a fourth step merit pay in March 1953.

Sledge was born in Southampton County and worked in the engine room of a tugboat after school when he was 10-years-old.

The Guide reported, “He is married to Eva Mae Harrell of Nansemond County (now Suffolk, Virginia) and lives in the 220 block of Chestnut Street in Portsmouth.”

♦♦♦

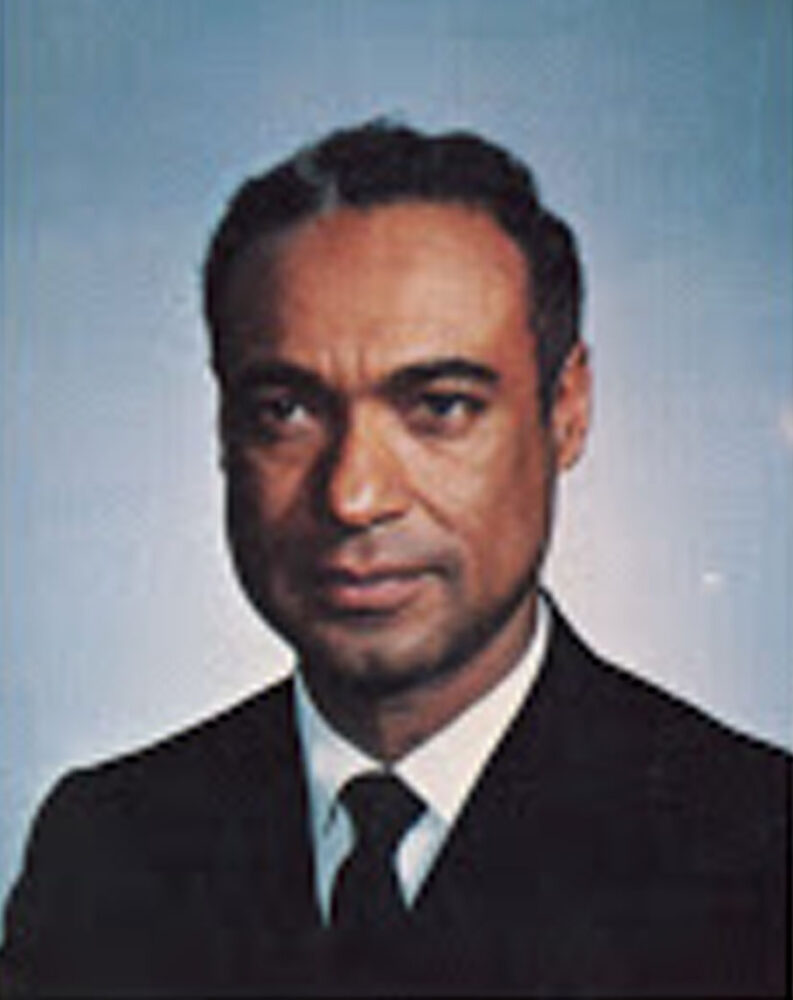

“Norfolk is Next Stop for Navy’s Senior Black Aviator” appeared in the February 20, 1971 edition of the GUIDE.

In an article by Milt Harris, a U.S. Navy journalist, a story read, “One of the Navy’s most senior Black Aviators and the third Negro in history to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy, Commander Reeves B. “Rip” Taylor relinquished his command of the Heavy Reconnaissance Attack Squadron Six (RVAH-6) February 6.

His new assignment would be to the staff of the Commander in Chief U.S. Atlantic Command and Atlantic Fleet’s Inspector General’s Office in Norfolk, Virginia.

This would have made Taylor one of the highest ranking naval personnel on the Norfolk Naval Base at a time when such high profile roles were rare for African-Americans.

According to the article, Taylor had served in the Navy for 17 years and “assumed command of the vigilante type aircraft reconnaissance squadron at its home base of Albany, Georgia in March of 1970.

“The unit received a number of honors for readiness. The squadron was deployed on its fourth consecutive combat cruise last year when they embarked about the U.S. Seventh Fleet carrier USS Kitty Hawk operating in the Western Pacific.

“Under Commander Taylor’s command, the squadron engaged in combat reconnaissance activities where they streaked off the 80,000 ton carrier’s deck during both day and night operations to collect pre-strike bomb assessment and electronic data over North Vietnam.”

The GUIDE reported that Taylor, who was a graduate of the Naval Academy’s Class of 1953, refuted the claim that he was only the third Black to graduate from the Naval Academy. He insisted that the number of Black graduates was higher.

“Negroes have been going in the U.S. Naval Academy since it opened, but its history is that only three have graduated during the academy’s 108 years, between June 1845 to June 1953.”

Taylor is quoted saying, “Prior to my appointment to the academy in 1948, seven Negroes had been admitted and two of them, Wesley A. Brown and Lawrence C. Chambers, graduated while I was in attendance.”

According to Tayler’s account, Brown was the first African-American to complete his training at the U.S. Naval Academy and graduated in June 1948.

“Prior to that five Negroes attended the academy – three of them John Henry Conyers, and Alonzo C. McClellan of South Carolina and Henry E. Baker of Mississippi were appointed during the Reconstruction period following the Civil War in 1872, 73 and 74 respectively,” Taylor said in the article.

Taylor said that two of the African-Americans had resigned and the third was dismissed.

According to Taylor’s account, “After 1875, no Negroes were in attendance at the academy for sixty years until 1936, when James Leo Johnson entered, followed in 1937 by George J. Trivers. Trivers resigned for reason of health. Johnson for his inability to speak in English and was deported.”

Taylor noted the Navy had been seeking to recruit more Blacks for the Academy.

He said when he was admitted to the academy 22 years earlier, he made the highest grade on the entrance examination out of 40 odd participants.

He was designated as a naval aviator in 1955 and served in reconnaissance and intelligence aviation most of his career and in the Western Pacific.

He was a native of Providence, Rhode Island. He had three children and resided in Albany, Georgia with his wife, Gloria Beaubien.

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter