Black History

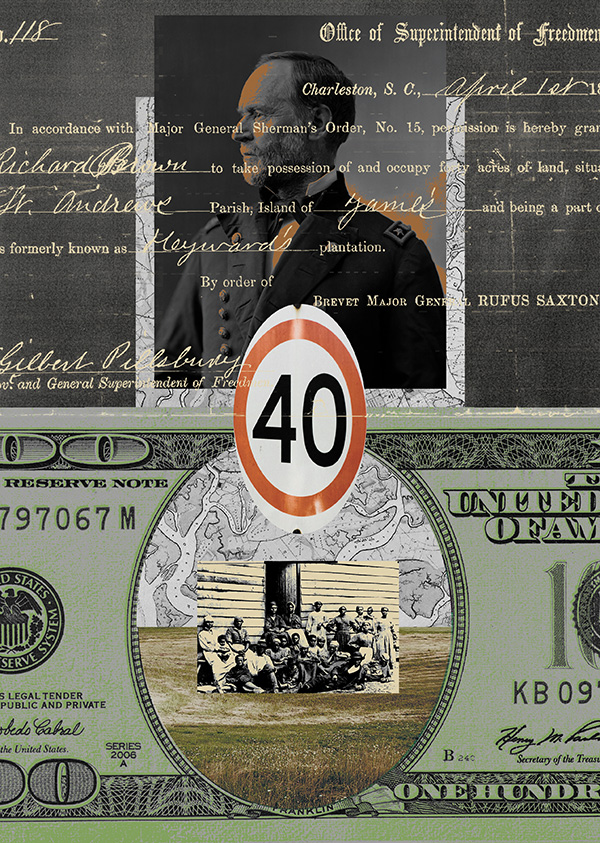

PART TWO: 40 Acres and a Lie

Despite early successes in land cultivation, freedmen faced devastating setbacks as President Andrew Johnson reversed policies and returned land to former Confederates, undermining the promise of 40 acres and a mule and hampering efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

#40AcresAndAMule #Reconstruction #BlackHistory #FreedmensBureau #AndrewJohnson #LandRedistribution

By Alexia Fernanandez Campbell, April Simpson and Pratheek Rebala

Mother Jones Magazine

July+August 2024

Special to the New Journal and Guide

Despite getting started late into the growing season, and having no mules or agricultural equipment, the freedmen were succeeding, shocking many of their former slave owners, (Gen. Rufus) Saxton reported back to headquarters in Washington, DC. “They have persevered with an industry and energy beyond our most sanguine expectations,” he wrote.

Life was far from perfect. For those who settled on the Sea Islands, such as Skidaway and Edisto, medical care was scarce. Those on the mainland faced the constant threat of white violence and little chance of justice if they fell victim to it. “The Negroes are frequently murdered, shot down in cold blood, without any provocation except their loyalty and because they assert their freedom,” Saxton relayed in a letter at the time.

“I hope and pray that our Government will not listen to the ex-parte statements of the old rulers of these States, many of whom are still traitors at heart, and even now are seeking to grasp again the political power under the old flag,” Saxton added. “It will be bad for the Freedmen if these men again get into power.”

It wasn’t long before Saxton’s fears became a reality. In April 1865, just a month after creating the Freedmen’s Bureau, Lincoln was assassinated by actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth.

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, was an avowed white supremacist who moved quickly to pardon many former Confederates and return their land.

“[Johnson] used executive power very, very skillfully to undermine transfer of land to Black people, and to really hamstring the Freedmen’s Bureau,” said Donald Nieman, a history professor at Binghamton University. He added that Johnson acted out of personal prejudice toward the freedmen, but also political expediency.

“By restoring land and by giving pardons to the former landowners in the South, he thought he could make that group of people beholden to him politically.”

General Oliver Howard, the head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, traveled to South Carolina in October 1865 and told the Black families gathered at a church on Edisto Island, south of Charleston, that the president had pardoned their former enslavers, according to the diary of a teacher who was there.

Howard suggested that the freedmen could work for the planters, urging them to lay aside bitter feelings and reconcile with their former enslavers.

“No, never,” the people murmured, according to the teacher’s account. “Can’t do it,” they said. They burst into song, singing about “wandering in the wilderness of sorrow and gloom.”

***

For more than a year, a battle raged over who was entitled to the land – the former Confederates or the formerly enslaved. Legislation that would have codified Sherman’s field orders into federal law made it through Congress, but was vetoed by Johnson.

The Freedmen’s Bureau resisted, insisting the property now belonged to the emancipated men and women. “They felt that they had earned the land. They’re the ones who had tamed the land, cultivated the land,” said Damani Davis, the archivist who oversees the National Archives’ Freedmen’s Bureau collection. “Their family and ancestors were buried in the land.

That prompted Johnson to dispatch two generals to ensure that the former slaveholders were reinstalled as landowners. By the time Congress took up another Freedmen’s Bureau bill in the summer of 1866, most of the land had been taken back. Lawmakers eventually mustered enough votes to override Johnson’s veto and pass a weaker bill that gave a few scraps to some formerly enslaved people who had received land titles and were still on that land.

The law swapped out their titles for warrants that allowed them to buy up to 20 acres for $1.50 per acre on government land in Beaufort County, South Carolina, far less than they had originally been promised.

***

In parts of the South, violence broke out as former rebels returned to plots that had since been occupied by the emancipated. One Freedmen’s Bureau agent reported that a 12-year-old boy had been “battered and bruised” by “his former master, who had driven him off, helpless and hungry, to find food and shelter as best he could.”

Armed members of the Ogeechee Home Guards revolted, landing several of them in jail. (“The declared intention of the Negroes is to make it impossible for white men to live in this section and then take possession of the plantation themselves,” the Savannah Morning News reported.) Many other freedmen on the South Carolina Sea Islands refused to work for their former enslavers.

Among the white Southerners trying to reclaim the rice plantations lost following the war was William Habersham, one of the previous owners of Grove Hill. In January 1866, nine months after Jackson received his 4 acres, Habersham swore his allegiance to the Union and sought a presidential pardon. He enlisted Dan Talmage, a well-connected friend in New York, to make his case.

“His former slaves wish to labor for him & he is willing to pay them wages or give them a fair share proportion of the crop,” Talmage wrote to one of his senators in Washington, DC. “I beg therefore that you use your influence to return him from his embarrassment. The season of planting is near and therefore important to get the matter arranged soon.”

While it is unclear if any of the formerly enslaved were truly interested in working for Habersham again, the appeals on his behalf worked. Within a few days, President Johnson pardoned Habersham, eventually allowing him to reclaim Grove Hill as his own.