Local News in Virginia

Part One: Remembering Black History As Norfolk Naval Base Turns 100

This year the nation and city of Norfolk will celebrate the 100th Anniversary of the opening of the Naval Operating Base Hampton Roads at Sewells Point, known today as Naval Station Norfolk.

The facility is the largest Naval base in the world and is part of the network of Navy, Marine, Air Force, Army, Coast Guard and other military units in the Hampton Roads area.

A key centennial date is June 28, when a presidential proclamation in 1917 set aside $2.8 million dollars for the development of Sewells Point into a naval operating base.

Construction began on a naval training center on July 4 of that year; and on October 12, 1,400 sailors marched from the training center at St. Helena across from the Norfolk Naval Shipyard all the way up to the new Naval Operating Base Hampton Roads at Sewells Point, where an official opening ceremony was held.

Since then, the facility has been the training, staging, planning and homeport for military operations involving millions of naval and other military personnel from the Spanish American War, World Wars I and II, the Korean Conflict, Vietnam and Desert Storm and many other conflicts involving the U.S. military.

But apart from its overall role as a fixture and symbol of the nation’s military light, there are many untold stories related to African-American military, civil rights and personal history.

African-Americans have worked in military or civilian capacities throughout the naval base’s existence.

While the Department of Defense and the U.S. Navy have many stories detailing Black history and the base, the Norfolk Journal and Guide Archives possesses thousands of stories – small and lengthy – doing the same, uniquely.

Guide stories date back as far as 1921, four years after the facility first opened. There are stories about Black workers doing various tasks, being honored for their long service on the base and its supply center as clerks and techs, Blacksmiths, to cab drivers, cooks and uniformed personnel at various levels performing a variety of roles.

The dark side of that history cannot be ignored, and the GUIDE recorded it, too.

There are stories about the challenges that Black civilian and military personnel, helped by the NAACP and other civil rights groups, encountered seeking access to equitable treatment, pay and employment.

The Guide recorded the strains which arose during the early days of desegregation between Black and White sailors on and off the base.

Among the most interesting facets of the base’s and Naval History was the fact that until the end of WWII, African-Americans and Filipinos were relegated only to the work of messmen and other laborious tasks.

The USS Mason was the Navy’s first naval vessel with a skilled Black crew whose maiden voyage was recorded for American history by Thomas Young, Journal and Guide photojournalist and son of P.B. Young, Sr., founding Guide publisher.

There were few examples of Blacks in high ranking military or civilian roles at the Norfolk facility which remained racially segregated due to policy until President Harry Truman issued an Executive Order killing that policy after 1948.

But it took a number of years before the policy was adopted and some form of diversity and adherence to civil rights for Blacks occurred on the base in the mid-1950s.

During the 1970s and 1980s, stories about the “first” Black high ranking officers and civilian officials began appearing in the Black and mainstream press.

♦♦♦

One of the initial bright spots of President Truman’s and the Navy’s efforts to move forward on race was illustrated in the April 1, 1950 edition of the Norfolk Journal and Guide.

“It’s Been Smooth Sailing Says Norfolk Base Wave” by Martha Hursey, who wrote about the first Black female sailor stationed at the base.

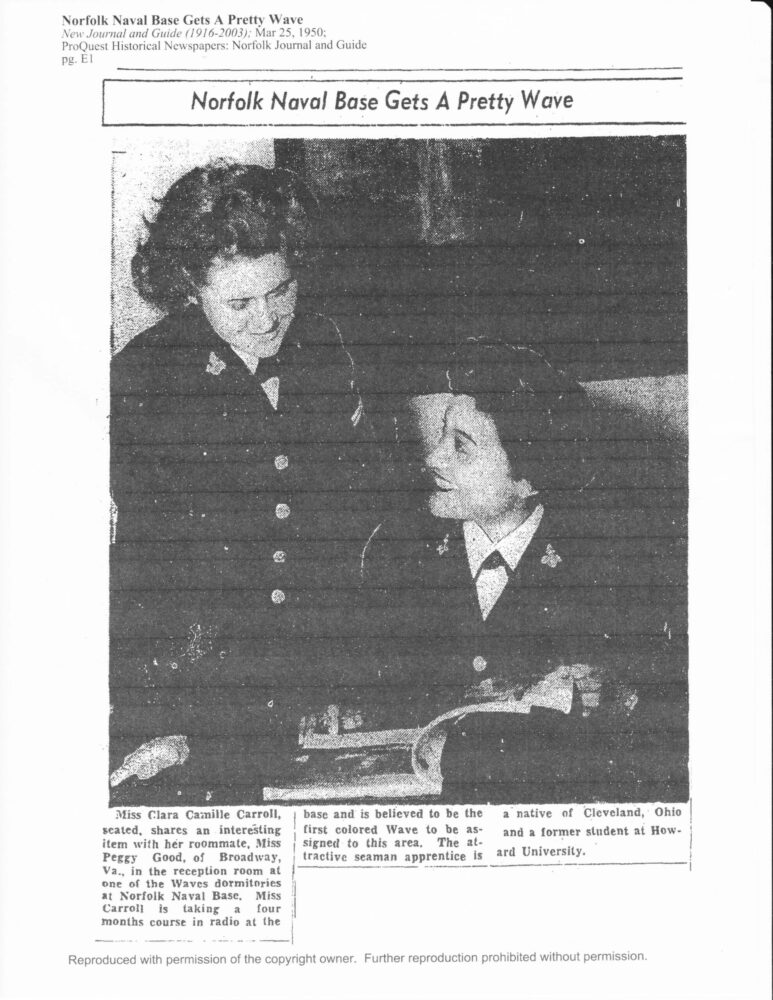

“For nearly six weeks, an attractive ex-Howard University student Clara Camille Carroll has been studying along with several other Waves.” The term (WAVE) was an acronym for “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service” and was the World War II women’s branch of the United States Naval Reserve.

According to the article, Carroll’s presence and studying at the radio school at the Norfolk Naval Base went “practically unnoticed except by fellow service women. So complete was her interrogation that even ranking naval officers were unaware that the Naval Base was host to the first colored Wave who hails from Cleveland, Ohio.”

Immediately after she finished boot camp in Great Lakes, Carroll was enrolled in the radio school here. Upon completion of the course, she was slated to be stationed on one of the several naval bases in the country.

The article noted Carroll said she enjoyed the various activities on the base when she was not involved in training. “The seaman apprentice said she is singing on the chapel choir at Frazier Hall making frequent visits to the Hobby Shop, the 12 cents movies and learning the game of billiards.”

“She has a roommate, Peggy Good from Broadway, Virginia, and they are constant companions. She said that she joined the Waves because they appeared to have a fine reputation and she liked the uniforms.”

The article continued, “In the city of Norfolk, she has not met with any difficulties either. She has gone everywhere and done everything that her fellow service women have.”

Carroll was quoted as saying, “I thought they were improving down here” (referring to the racial climate of the South).

The naval base’s first “colored Wave,” Clara Carroll, joined the military the previous August, according to the article. Before enrolling at Howard in Sociology, she lived in New York City for two years where she worked for the city’s Housing Authority. She had plans to join the Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) sorority “in the coming years after a long career in the military.”

♦♦♦

In the April 19, 1952 edition of the Norfolk Journal and Guide, a headline appeared “Navy Declines Norfolk’s NAACP’s Pleas on Race Signs.”

“Efforts will be made to obtain from President (Harry) Truman a ruling regarding the refusal of Naval authorities to act favorably upon a request of the Norfolk Branch of the NAACP that signs designating racist use of certain facilities at the two major local Naval Installations be removed.”

Jerry O. Gilliam, the Norfolk NAACP Branch President, was working with the National office of the civil rights group to seek a ruling “from the President as to whether the mores and customs of a community can extend to the federal government and its holdings.”

According to the article “The request filed by the local NAACP noted complaints by colored civilian Naval employees protesting signs reading ‘White’ and ‘Colored’ posted at rest rooms, drinking fountains and recreational facilities at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard and the Norfolk Naval Base.”

The complaint said the signs were humiliating to the “Negro employees.”

Navy officials refused to remove the signs because “Naval industrial relations take their cue from local customs,” and Norfolk like most of the South was still adhering to Jim Crow segregation of public facilities.

“The Negro sailor,” said the NAACP letter to the Secretary of the Navy, “is humiliated when after a trip probable to Korea, he is faced with such signs when they return home.”

“These signs are a definite impediment to the productive effort of the command because they give everyone who has a white skin a superiority complex, that makes him unfitted to meet the man with the a Black Skin.”

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter