Virginia Political News

Part IV: Black History Month – A Local Montford Marine Recalls That Time In History

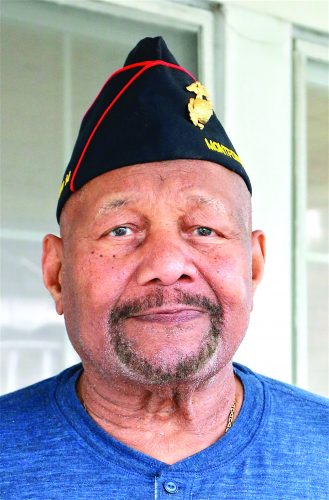

Nathaniel E. Harris is a member of a very small, unique and shrinking group of African-American men.

Harris, who lives in Portsmouth, is among the remaining 300 or so Black men who were the first to endure boot camp to prepare to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps at Montford Point Camp, near Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

[cs_content][cs_element_section _id=”1″][cs_element_row _id=”2″][cs_element_column _id=”3″][cs_text _order=”0″]

Nathaniel E. Harris is a member of a very small, unique and shrinking group of African-American men.

Harris, who lives in Portsmouth, is among the remaining 300 or so Black men who were the first to endure boot camp to prepare to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps at Montford Point Camp, near Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

These famous Marines received a Gold Medal from President Barack Obama for being among the first group of Black men to serve in the Marine Corps.

Blacks were barred from serving in the Corps until 1941, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order five months before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered WWII. The Corps was the last branch of the military to admit Blacks.

There was resistance.

Maj. Gen. Thomas Holcomb, the Marine Corps commandant at the time, is quoted as having said, “If it were a question of having a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 Negroes, I would rather have the whites.”

African-American recruits were not sent to Parris Island, South Carolina or San Diego, California, but to Camp Montford Point, N.C.

The Marines who trained there between 1942 and 1949 helped pave the way to the modern Marine Corps.

Sixteen-year-old Nathaniel E. Harris said he arrived at Montford Point in July 1946, almost a year after WWII ended when the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on two cities in Japan.

He was born in New York City, but was shipped to Portsmouth to live with his grandparents in the Truxton section of Portsmouth after the death of his mother.

Harris said that movies and the tales of Black Marines who returned from WWII perked his interest in signing up for the Corps. Plus, it was a way to escape Jim Crow Portsmouth.

“There was nothing but trouble here in Portsmouth at that time for a Black man,” he told a GUIDE reporter recently. “Racial profiling? That was everywhere and for everything. So I was glad to go see the world. We were aggressive and adventurous … see the world and the Marine Corps was my ticket.”

When he arrived at Montford, it was two years before President Harry Truman issued an Executive Order desegregating the U.S. Military. During WWII Black Marines were assigned to segregated units or were relegated to support roles such as cooking and cleaning for officers or moving around tons of ammunition.

“We lived in 10 quonset huts lined up neatly in a row in an isolated area far from the main base,” Harris recalled. “The White guys had the nice barracks and clubs about eight miles way at Camp Lejeune.”

He was in the 10th Platoon, with 36 other young Black men.

There were only White officers and Black Drill Instructors (DIs) and other Non-commissioned Officers by the time Harris arrived.

According to Harris, many of the Black Drill Sergeants (DIs) were former Army or Navy personnel, who during WWII, had some combat time in ammunition storage companies.

The most noted was Sgt. Maj. Gilbert “Hashmark” Johnson – so nicknamed for his many service stripes. He became one of the first Black DIs in the Marine Corps.

Harris said that by the time he arrived, “Hashmark” Johnson was the senior enlisted personnel assuring that the Black DIs under him trained their men well.

The site where Camp Montford Point existed has been renamed in Johnson’s honor.

“He was hard and fair. He wanted us to make sure we did well,” recalled Harris. “He wanted us to make this best of our opportunity in the Marine Corps. Proud to have met him.”

Montford sat a distance from Camp Lejeune and a distance from the mostly White city of Jacksonville, North Carolina.

Harris said the racism he encountered in Jacksonville was more harsh than Portsmouth and “probably worse than what one would have encountered in Mississippi at the time.”

Harris said while the White recruits were granted “liberty” after completing boot camp at nearby Jacksonville, Black Marines had to travel about 12 miles to the all-Black community of Kinston, North Carolina to “muster” and socialize.

Harris’ first tour duty was to the “7th Afro-American Draft” with all-White officers in Guam and Saipan, the collective of islands near the Japanese mainland.

“Many of the Black soldiers were also assigned the task of looking for Japanese soldiers who did not know the war was over and were still hiding out in the hills on Saipan and Guam,” Harris said.

“They were also assigned to units loading and unloading ammunition, and they manned a Triple A Anti-craft company.”

Even after 1948 when the Armed Forces were integrated, Black Marines were still disrespected by White colleagues. There were few Black officers and access to technical schools and advancement had racial barriers.

But by the time he left Japan, Harris said he was seeing progress in the Corps. He saw more Black men being advanced in ranks, attending tech schools and being respected as enlisted non-commissioned personnel.

“I started going to school that opened up in basic education,” he said. “I passed my high school basic test, started college and attended other schools in mine warfare, engineering, shooting, drilling and teaching basic and advanced information needed by Marines.”

Back in the states, he said, he was part of a 26-member Marine singing group. It toured by bus.

His group performed on the radio, TV and he once sang for Queen Elizabeth II in 1962 when she visited the USA.

He also taught basic math to Marines at the Engineering School Courthouse Bay at Camp Lejeune.

Harris is a co-founder of the NCO Leadership School at Quantico, Virginia for Non-Commissioned Officers.

But apart from his Marine Corps pride and other assets, Harris said he has been addressing some health issues due to his service overseas.

He retired in 1967, but before he left service he began to experience some unusual physical ailments.

He is among the thousands of U.S. servicemen and civilians inhabiting Guam who were exposed to high doses of Ionized Radiation. It has caused the enlargement of his skull, leg spasms, cancer of the prostate, and nerve deterioration in his legs.

It was only after the left the Corps that the symptoms to radiation became more prominent and damaging.

He has been taken for study and observation at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). A piece of legislation, H.R, 160 is moving through Congress designed to address such health issues by veterans.

He has been battling the Veterans Administration and other officials for the past eight years, Harris said. Though some veterans have received restitution, he has not for his ailments, including exposure to tainted water at Camp Lejeune.

While he is alert mentally, Harris, who is 88, said he is slowly losing physical mobility.

He remains active with his various enterprises, including writing an informal memoir for his grandchildren recalling his civilian and military life and accomplishments.

“I am very proud of my opportunities and contribution to Black history, and representing the U.S. Marine Corp,” said Harris. “I did it for family and country. But I also think the government should step up and compensate me for the damage they inflicted on my body while I served and was not aware of it.”

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

[/cs_text][/cs_element_column][/cs_element_row][/cs_element_section][/cs_content]