Hampton Roads Community News

Negro League Baseball Observes Its Centennial

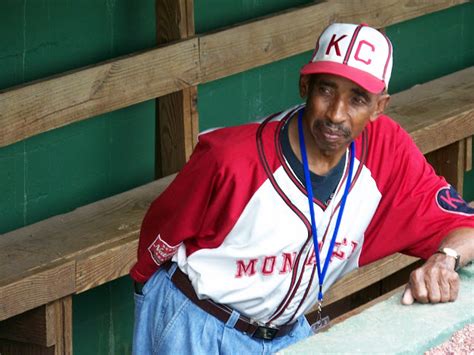

The GUIDE Salutes Leaguer Sam Allen of Norfolk

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

This year’s abbreviated season of professional baseball due to COVID-19 can’t underplay that it is still the 100th anniversary of the Negro League Baseball.

This year’s abbreviated season of professional baseball due to COVID-19 can’t underplay that it is still the 100th anniversary of the Negro League Baseball.

In August, according to the sports website “The Ringer”, Major League Baseball celebrated the centennial of the founding of the Negro National League, the first of the seven segregation-era circuits formed during the 1920s or 1930s that have collectively come to be labeled “the Negro Leagues.”

Players, managers, coaches, and umpires received the Negro Leagues’ 100th-anniversary logo and Negro Leagues–related programming was on display.

The league-wide celebration, which was originally scheduled for June 27, is part of the year-long “A Game-Changing Century” initiative,

conceived by Kansas City’s Negro League Baseball Museum. Although the pandemic delayed the day of recognition, forced the museum to close for three months, and postponed other plans until 2021 (when the museum will spearhead a program dubbed “Negro Leagues 101”), 2020 has been a big year for honoring the Negro League Baseball’s legacy.

Norfolk and Hampton Roads have their own Negro League Icon, Sam Allen, who is known to many around the area.

Now, at 84-years of age, Allen checks off items on a noticeably short to-do list: breakfast with buddies whenever possible due to the pandemic; warming the seat of his favorite recliner, or an occasional stint laying floors and carpet.

Unlike previous years, Allen is unable to attend any of the Norfolk Tides baseball games, again due to the pandemic.

Allen, who is Hampton Roads’ living and breathing contribution to the Negro Leagues, is always eager to share his memories.

Allen played for three teams of the now extinct Negro Baseball League (NBL); one of 60 men who can make that claim and are still living.

Willie Mays, 87, who played in the NBL and in the Major League Baseball (MLB), is among them.

Black players have played baseball since its inception in this nation during the 1850s.

But a racist “gentleman’s agreement” barred them from playing with white professional and amateur baseball teams during the early days until 1947 when Jackie Robinson desegregated the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In 1920, Rube Foster founded the Negro National League (NNL) to give talented Black players an outlet to play

An enterprise of Black ownership, its early financial success prompted the formation of the Eastern Colored League in 1923. The two

circuits converged to play the World’s Colored Championship in 1924 and continued the annual series until 1927.

After the desegregation of Major League Baseball (MLB), the Negro Baseball League’s pool of talented Black players and fan base began to shrink.

By 1951, the sun had begun to set on the Negro league and 14 years later it folded.

***

Allen grew up in Norfolk during the period baseball leagues were segregated.

“I started playing when I was six-years-old with the bigger guys in the Lindenwood and Barraud Park section of Norfolk,” said Allen. “I played with guys like Walter Lundey and James Sweat, who

also had careers in the Negro Leagues and white majors.”

Allen recalls the various sites where the Black teams played recreational and semiprofessional baseball, such as the Community Field, in the Bruce Park section of Norfolk off Maltby Avenue.

There were fields in Lindenwood on Pollard and Barre Streets, Berkley’s Lincoln Field, Lambert’s Point and Carver Park where the giant U.S. Postal facility exists now off Brambleton Avenue in

Norfolk,

At times Blacks played at High Rock Park, which is gone now, but sat at the intersection of Church Street and Rugby Streets. It was the home field of the all-white Norfolk Tars, once a New York Yankees

farm time.

Allen recalls the semi-professional teams

carrying the names of the Norfolk Eagles, Tigers, Battling Palms, South London Bridge Sluggers, Aces, the West End Giants.

When Willie Mays was stationed at Fort Eustis, he organized his All-Star team in 1952-1953 which,

Allen said, played local teams in Lynchburg, Winston-Salem, and at Community Field in Norfolk on the weekends.

***

In 1956 Allen said he got connected with the Negro League network and got a year playing for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro League.

Memphis, Kansas City, Detroit, and Birmingham, at that time, were the only Negro League teams left. Many of the league’s players were holdovers from its glory days of waiting for a call from a Major League Baseball team.

The next season he was off to Douglass, Georgia. He had been invited to try out for a farm club of the Cincinnati Reds, as the MLB was ramping up its recruiting of Black baseball talent in the mid-50s.

At the same time, planeloads of players from Cuba arrived, having been invited to MLB Spring Camps before this operation was shut down by the island nation’s government after Fidel Castro took over.

Allen said the Cuban talent was so good, he got cut from the Cincinnati Camp.

He then called Negro pitcher and talent agent Bobby Mitchell, who worked for the Kansas City Monarchs.

Allen was told the Monarchs needed players and had a training camp in Jacksonville, Florida.

The team was getting ready for its first series of games in Charleston, South Carolina.

“I had $25 in my pocket and I bought a $19 ticket to Jacksonville, Florida,” Allen recalled. “The Jacksonville team was training with the Monarchs and they only had three players. The Kansas City coaches allowed me and several other players to fill the Jacksonville roster so a game could be played.

Allen recalled he got a single hit, struck out, and then hit one for a homer. The makeshift Jacksonville team beat the Monarchs, who offered him a contract.

When the Monarchs arrived in Charleston,

the hotel was filled, but they found a room at a hotel near the Naval base in the city in the spring of 1957.

“I was dog tired,” recalled Allen. “I had not slept for three days and finally got some rest before the game in Charleston. We then got on the road to barnstorm through Daytona Beach, Mobile,

Ala., eventually landing in Longview, Texas then Shreveport, La.

“When we were not traveling, sleeping and finding a place to eat, we were playing,” said Allen. “We would play doubleheaders Friday and Saturday and doubles and triples on Sunday. Those were big crowds which pulled in money. Many days I prayed for rain to get a rest. I was tired but I was having fun.”

***

The Negro League teams did not travel by air or train transportation. On average it took four days to travel from one city to another. A crowded, messy, and loud bus was their home away from home.

“Many times, we slept on the bus when we could not find a hotel,” said Allen. “We all had to share one bathroom when we were in a hotel.

“There was no place to wash your uniform and they got really dirty and funky. At times we would arrive in town, and in two hours we had to wash our bodies and our uniforms before a game.”

The teams played games at various parts of Texas, then rolled northward to Detroit where Blacks were in each locale.

Then they traveled to rural parts of Indiana, Montana, North Dakota, Idaho, and Wisconsin where there were no Black people, but little Jim Crow racial tensions.

***

“The Monarchs would travel with other teams like the Detroit Stars,” he said. “In out of the way places where there were no Blacks, we played mostly white teams before all-white fans or native

Americans.

“At the time there were no playing fields,” he continued. “I recall we had to cut down a stand of trees and create one and even string the lights.”

Allen recalled playing at the Sioux Indian Reservation in Paradise, South Dakota, near Mobridge, where Sitting Bull was incarcerated and eventually “killed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs”,

according to the people in the area.

Back down South, the Monarchs played other Negro League teams in small villages and towns in Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, and eastward

to the Carolinas.

Allen spent one year with Kansas City. Willard Brown was summoned back to the team, and Allen was cut.

In 1958, he found a job with Raleigh and then with Memphis, during its final year of that team’s operation, in 1959.

In 1960, Allen’s professional baseball career ended, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army.

***

After two years, two months, and 10 days, Allen was out of the Army and back in Lindenwood, working and still playing baseball for fun when he could.

By 1965 the Negro Leagues folded as the best Black baseball talent had become dominated by the MLB.

For years Allen attended all-star games, conventions and got involved with other programs related to the old NLB. He was a regular

at the Larry Lister Foundation’s gathering: the last one was held in Portsmouth.

He has been inducted into the Negro League Baseball and MLB Halls of Fame and gets all the perks which comes with induction.

“Although I played during its final years, I was blessed and proud of being a part of that history,” Allen said. “Those players were great, because the league gave guys like me a chance to show their talents.

“It is only a few of us left, but I hope when I die the memory and legacy of the Negro League will not be forgotten.”

TWO PICS ATTACHED

You may like

Virginia House Speaker To Keynote NSU’S 112th Commencement

Disbanding of TSU’s Board of Trustees: An “Attack On DEI”

THE PATH OF TOTALITY: If You Missed It, Catch Next One In 20 Years!

Hampton Roads Delivers Another Successful UNCF Mayors’ Masked Ball

Baltimore Bridge: A City’s Heartbreak, A Nation’s Alarm

A Conversation With New Journal & Guide Publisher