Local Voices

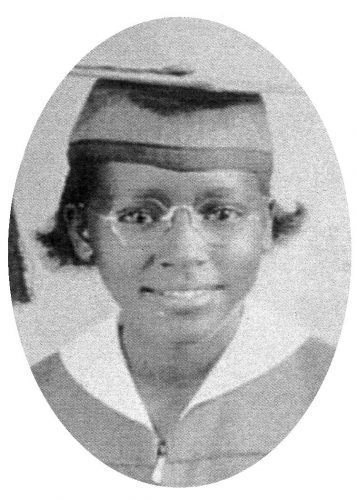

Mrs. Lillian Trotman: Turning 100 In A New Decade

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

To view events on the timeline of African-American history since 1920, historians and journalists rely on the contents of books or mine the internet.

But a small number of people still live with us who witnessed firsthand, their own trials and successes over the past 100 years.

Mrs. Lillian Vernell Charles Trotman of Virginia Beach is a fine example.

Her 100th birthday is on January 18.

Mrs. Trotman believes the Almighty and “staying busy as a homemaker and parent contributed to her longevity.

She was born in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. Trotman’s parents, Albert Charles and his wife, Ella, moved to then Princess Anne County (now Virginia Beach) with Lillian and her brother Albert, Jr. in tow.

She recalled that her parents and her siblings lived on the Oldes farm, where her father was hired as a hand to attend to the animals.

Her parents, especially her mother, were strongly convinced about providing an education for their offspring.

But in the mid 20s, in Princess Anne County, Black families had few options to achieve that lofty goal.

While the county provided some educational opportunities for white families, there was only a two-room shack for Black children of all ages.

“Albert and me had to walk to that makeshift school two miles every morning to Great Neck,” she recalled. “Mother said we had to go to school whether it was rain, sleet or snow. She was serious.”

Every morning she recalled a man would deliver two teachers from Norfolk to the school and “they taught everything.”

Trotman recalled one winter morning, she and her brother walked the two miles in frigid temperatures only to find that it was so cold no one was at the school, including the teachers.

“We had to walk back home. It was so cold, God, I was crying and freezing,” she recalled. “But this lady invited us into her home to get warm. She rubbed my hands and we stayed long enough to get warm. Then we walked the rest of the way home. I will never forget that day.”

After completing her studies at the makeshift school, the family moved back to North Carolina for a year.

When the clan moved back to Princess Anne County, she was enrolled in the school at Union Baptist Church. It was the only school to provide some high school training for Black children.

Black parents’ effort to secure funding from the county for a traditional school building to educate Black children were ignored.

So the Black community used the Union Baptist Church’s Great Hall and its sanctuary as space to educate their children, with two teachers, teaching every course.

Black families in the county, according to Virginia Beach Historian, Edna Hendrix, eventually raised enough money by selling dinners, passing the hat in the community and, in 1934, receiving a grant from the Roosevelt era-Work Progressive Association (WPA) , to buy land and build the Princess Anne County Training School.

The school was the forerunner of the Union Kempsville High School. Margie Coefield is a member of the Alumni Association. The group was organized to preserve it, including the elementary school.

The Union Kempsville High School was closed in 1969 due to desegregation and in the late 90s, despite protest from alumni to preserve the city’s first Black high school, it was torn down.

Today the Renaissance Academy at Cleveland and Witchduck Road, sits on the land where the school once existed. Inside the facility is a museum, dedicated to preserving the legacy of the school.

Coefield was the chairperson of the committee set up organize and collect the exhibits on display in the museum which opened in 2010.

Coefield, who is organizing Trotman’s centennial celebration, first met Mrs. Trotman in 2007. She also organized the “Last Commemorative” of Union Kempsville Alumni, prior to the old school’s demolition.

She said that she was fascinated by Trotman’s recollections of stories of life for Blacks in old Princess Anne County.

But Mrs. Trotman graduated in June 1938, before the newly constructed Union-Kempsville High School officially opened later that fall.

Trotman’s graduating class received their diplomas from a school official standing at Union Baptist’s pulpit.

Then it was off to college for Mrs. Trotman, in Norfolk at the Norfolk Unit of the Virginia Union University, (VUU) which sat in the basement of the Hunton YMCA. It is called Norfolk State University now.

“I can’t remember what I was going to major in,” she said. “But I had one book. I could not continue because my parents ran out of money.”

She landed a job as a maid, one of few jobs available to Black women of any age in Pre-WWII Virginia. She also worked on the housekeeping staff at the Cavalier Hotel in Princess Anne County.

Then she met her husband John Jefferson Trotman, who was a handyman and worked as a waiter at the Cavalier.

The couple worked to secure a home in Greenhill Farms. The Trotman union eventually produced seven sons and one daughter.

“We had no furniture. So I built it for us using my own hands, wood, hammer, and nails,” Mrs. Trotman recalled. “I built the living room furniture, and the furniture and beds for my our bedrooms. This allowed me and my husband to use our little money for other things.”

World War II arrived and her husband served in the U.S. Army for two years.

“I had to carry on with two children and run a home,” Mrs. Trotman recalled.

In the midst of WWII and over a decade before Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks stood their ground on a street bus, Trotman had her moment.

But she was not arrested.

“I got on a bus at London Bridge with my two young sons,” she recalled. “The bus was not full. But the driver insisted that I go to the back of the bus. Well, I refused. I got off with my children.

But before I did, I told him they are doing this while my husband was overseas fighting for their freedom in this country. We then walked from London Bridge to Oceana.”

Mrs. Trotman said that much has changed since 1920. Jim Crow segregation is dead; so are the segregated schools and other overt acts of racism. Black women have more career options than homemaking and being maids.

She can’t recall when she first voted. She does recall the day in 2008 when she cast a ballot electing the first African-American President Barack H. Obama.

“I don’t know how much longer I have to live,” she said. “I will be 100 years old…which is a blessing. I have lived this long by living a Godly Life and listening to His teaching. If you do that…you will live a good and full life as I have.”

Coefield and the Alumni Association are collecting the names of other 1938 Union Kempsville graduates and afterwards as part of its historic registry. Please contact her at margiecoefield@cox.net.