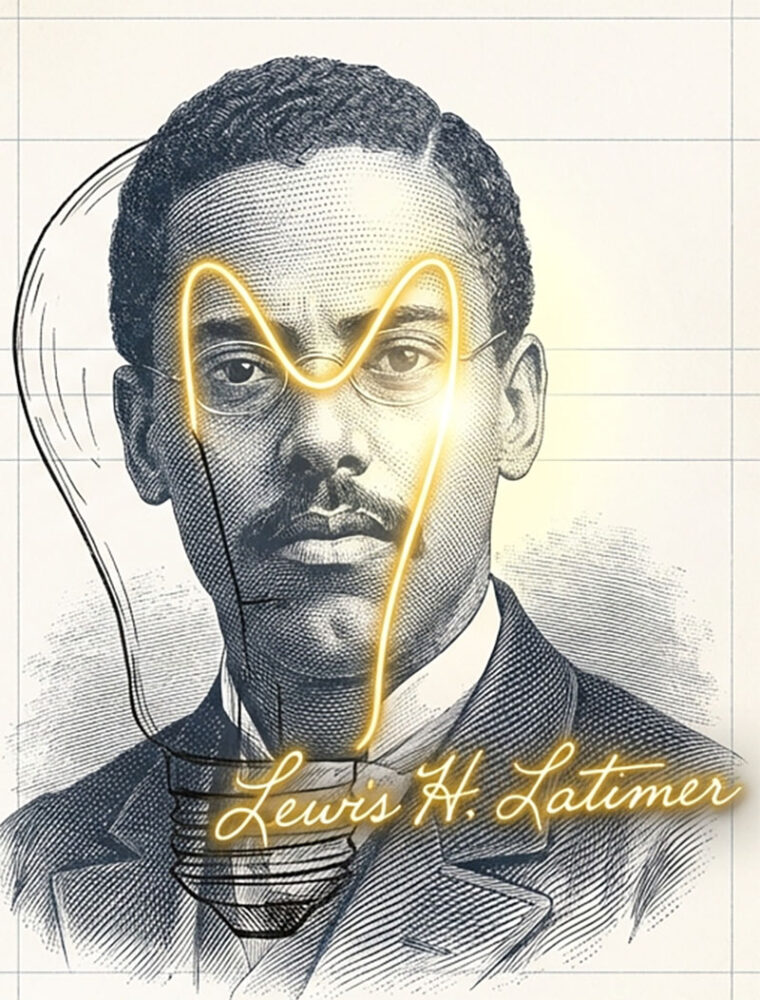

Black History

More Than a Footnote: How Lewis Latimer Helped Build the Modern World

Lewis Latimer was more than an assistant to famous inventors. He helped secure the telephone patent, made the lightbulb practical, defended electrical patents in court, and quietly shaped the infrastructure of the modern world.

#LewisLatimer #BlackHistory #BlackInventors #STEMHistory #HiddenFigures #TechInnovation #AfricanAmericanHistory #Edison #InnovationMatters

History often celebrates the “lone genius.” We are taught to credit Thomas Edison for the lightbulb and Alexander Graham Bell for the telephone. But between invention and global impact stands another kind of innovator—the practical architect who makes bold ideas usable, durable, and accessible.

Lewis Howard Latimer was that architect.

Born in 1848 to parents who had self-emancipated from slavery in Virginia, Latimer’s life began in the shadow of injustice. His father, George Latimer, was arrested in Boston for “stealing himself” from enslavement. A public fundraising campaign purchased his freedom for $400. From that foundation of struggle, Lewis Latimer rose to help construct the infrastructure of modern America.

His fingerprints are on the technologies that reshaped the world.

He Helped Secure the Telephone Patent

In 1876, the race to patent the telephone came down to hours. Alexander Graham Bell needed precise technical drawings to solidify his claim. Latimer, a skilled draftsman working at a Boston patent law firm, translated Bell’s rough sketches into the detailed blueprints required by the U.S. Patent Office. His accuracy and speed ensured Bell’s patent filing was complete and defensible. Without Latimer’s expertise, history—and ownership of one of the most transformative inventions ever—might have turned out differently.

He Made the Lightbulb Practical

Edison’s early lightbulb worked, but barely. It burned out quickly and was too fragile for mass use. In 1882, Latimer patented a more efficient method for manufacturing carbon filaments, dramatically increasing durability and reducing cost. His process made electric lighting practical for homes and businesses—not just laboratories.

Latimer understood what this meant. Electric light, he wrote, was as welcome “in the palace as in the humblest home.” He saw technology not as spectacle, but as social equalizer.

He Supervised the First Electrical Systems

Blueprints mean nothing without infrastructure. Latimer oversaw installation of early public lighting systems in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. In 1881, he was sent to London to rehabilitate a struggling electric light factory. Facing racial hostility and operational chaos, he reorganized the plant, mastered the chemistry of glass and filament production, and made it functional within nine months. He exported American electrical standards to Europe—while navigating discrimination as a Black supervisor in the 19th century.

He Defended the Industry in Court

Latimer later joined Edison’s inner circle and became the only Black charter member of the elite Edison Pioneers. But his role went beyond symbolism. As a patent expert and investigator, he helped defend Edison’s claims during fierce “patent wars.” His technical knowledge and courtroom testimony protected the intellectual property that stabilized the young electrical industry.

He Was a Creative and Civic Leader

Latimer was more than an engineer. He was a poet, musician, painter, and author. In 1890, he wrote Incandescent Electric Lighting, a clear, accessible guide that helped the public understand the new electrical systems transforming their cities.

Outside the lab, he advocated for civil rights and education. He taught mechanical drawing to immigrants, supported job training programs for Black women, and pushed for greater representation in public institutions. He believed progress required both innovation and justice.

He Invented for Everyday Life

His patents also addressed daily concerns—from improved sanitation systems for railroad cars to early air-cooling and disinfecting devices. Latimer focused on practical solutions that improved quality of life, not just headlines.

Today, the Lewis Latimer House Museum in New York preserves his legacy. But his greater monument is everywhere: in the glow of a light switch, in the legal foundations of the telephone industry, in the infrastructure of electrified cities.

Lewis Latimer was not a footnote to history’s giants. He was the bridge between their ideas and our reality. The modern world did not simply appear—it was engineered, refined, and defended by minds like his.

And the question remains: how many other architects of progress remain hidden in the margins, waiting for their story to be fully told?

Local News in Virginia5 days ago

Local News in Virginia5 days agoTony Brothers: In The Zone

Black History5 days ago

Black History5 days agoMaking History Again During Women’s History Month

HBCU5 days ago

HBCU5 days agoCharlie Hill Makes Historic Gift Of $1.5M To VSU

Local News in Virginia5 days ago

Local News in Virginia5 days agoBridge Corner – 3.5.26

Black History4 days ago

Black History4 days agoVirginia Women Who Shaped— And Won— Fight For Voting Rights

National Commentary4 days ago

National Commentary4 days agoThe War of Choice

Civil4 days ago

Civil4 days agoDigital Download: Not All A.I. Is Created Equal

Civil3 days ago

Civil3 days agoVoter Alert: A Trump Executive Order Could Seek To Alter Midterm Victories

You must be logged in to post a comment.