Hampton Roads Community News

How Va. Textbooks Handled Slavery History For Generations

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

On the first day in office, Virginia’s new Governor Glenn Youngkin issued 11 Executive Orders. One of them ordered the end of the use of divisive concepts, including Critical Race Theory, (CRT) in public education.

On the first day in office, Virginia’s new Governor Glenn Youngkin issued 11 Executive Orders. One of them ordered the end of the use of divisive concepts, including Critical Race Theory, (CRT) in public education.

Political and academic critics of the Governor’s order say he is seeking to impose a solution to a problem which does not exist. CRT is not taught by any of the 132 School Public school Divisions in Virginia.

CRT is the post graduate study of how the United States has used legislations, laws and institutional policy to abuse and discriminate against African Americans.

Further Civil Rights activists and parents say the Governor is joining the chorus of White conservative Republicans seeking to deter teaching of history, especially as it relates to African Americans.

Opponents of the Governor’s edict depict “divisive concepts” as descriptions of slavery and other physical and legislative abuses of Black people historically.

White conservatives have said publicly that the discussion of such issues would cause racial division and impose guilt on White children for the actions of their ancestors.

Educators, activists and even school officials believe the anti-CRT effort may lead to a “white-washing” of the life of Blacks, prior to the Civil War and the era of Jim Crow segregation. But years ago Virginia achieved this goal in a 7th grade textbook used in the classrooms as late as the 1950s.

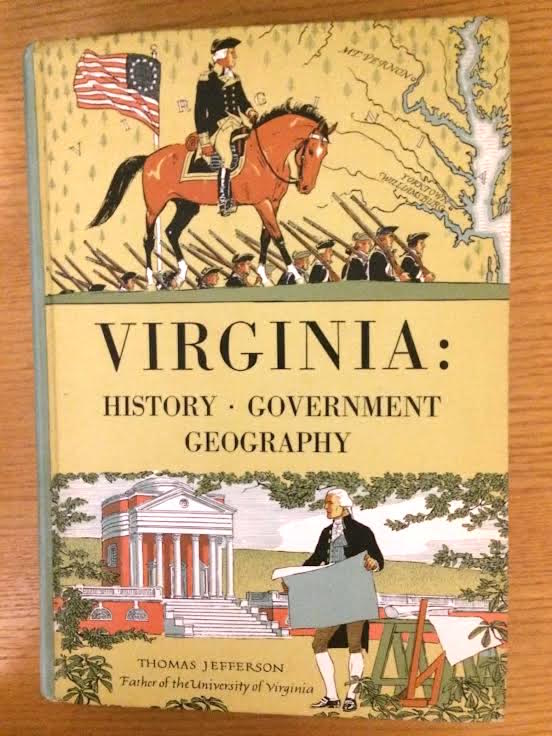

In Chapter 29 of the textbook “Virginia: History, Government, Geography. ” there are over 10 pages in Chapter 29 devoted to the subject of “How the Negro Lived Under Slavery: Slave Laws Not Strictly Enforced”. A copy of the first two pages were posted on Facebook last week, and the GUIDE, spotted it.

The GUIDE called the Library of Virginia Reference Department and had a Librarian track down the textbook. Considering the brutal history of how Blacks were captured and transported in masses from Africa to American enslavement, and also the scheme to export them abroad during the Colonial period to the 1840s, the wording and imagery related to the narration on pages 368-376 of the school book were not only unbalanced, but decidedly deceptive.

On page 368, the image depicts a White man clad in antebellum dress warmly bidding farewell to a Black family he has freed as he sees them off to Liberia, a settlement in West Africa.

Along with the Black father there is his wife and four children – two boys and two girls. They are dressed in formal antebellum wear.

The text reads, “’Early in Virginia history, the General Assembly made laws closely controlling the Negroes. However, the laws were not fully enforced. Many slave masters did not like to have the state government meddle in what they considered their private business. They managed their ‘servants’ according to their own methods, they knew the best way to control their slaves was to win their confidence and affection.”

According to the school book used to teach history to thousands of Virginia students, “many Negroes” were taught to read and write. Many of them were allowed to meet in groups for preaching, for funerals, and for singing and dancing.

Further, they went visiting at night and sometimes owned guns and other weapons. The treatment of Virginia slaves depended upon the character and the common sense of their masters, according to the textbook.

“It cannot be denied that ‘some’ slaves were treated badly, but ‘most’ of them were treated with kindness,” according to the book.. “Public opinion in Virginia frowned on harsh masters.”

The narrative continues on page 369: “A feeling of strong affection existed between masters and slaves in a majority of Virginia homes.”

Richard T. Barton of Winchester, whose father had freed his slaves and sent them to Liberia, wrote of the parting between his father’s family and the families of the freed Negroes: “I was quite a small boy at the time, but I remember the incidents perfectly. I recall the weeping family that parted with these servants who were very dear to us.”

Another slave owner, Thomas Herndon freed his slaves and tearfully saw them off as they departed for Liberia. “He was on shipboard to tell his servants a last good-by. When the master began to speak he became so choked with feeling he could hardly speak. The tears in his eyes brought a warm response on the eyes of his departing servants.”

Said Mr. Herndon: “My heart is too full. I can hardly speak. You know how we have lived together. Servants, hear me. We have been brothers and sisters. We have grown up together. You are now on the point of starting for the new land of your ancestors.”

Along with their freedom and a warm send off, the text noted that Mr. Herndon gave one Black family $2,000 to procure “everything we could think of to make you comfortable — clothing, bedding, implements of husbandry, mechanics, tools, books for the children, etc.”

***

This scene depicted in the history book for Virginia students offered some exaggerated truth in that there was an early effort to export Blacks back to Africa by some Whites.

An organization called American Colonization Society, with funding from Congress, was established to organize the exodus from the United States to the Colony of Liberia, in West Africa.

The first wave of formerly enslaved people in the United States to resettle in Liberia were from New York.

Kidnapping and enslaving people from Africa was abolished in the United States in 1808, though the practice of keeping people and their children enslaved was still legal in many states and slavery would continue until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

One of the prominent free Blacks who emigrated to Libera was Norfolk-born Joseph Jenkins Roberts who left with his mother, wife, siblings and children. He was a freed Black merchant who emigrated to Liberia in 1829. He was elected the first and seventh President of Liberia after independence.

The effort to export Blacks back to Africa was a double-edged sword. As more Blacks were freed or escaped from plantations, fear grew among Whites of rebellion and a belief that Blacks would seek social equity and compete for political and economic power.

Any movement to dispatch Blacks to Africa or any place out of the U.S. subsided after 1831 and the Nat Turner-led slave rebellion in Southhampton County, Virginia.

Also, the liberal allowance of Blacks to gather for worship or to socialize, own land, weapons and move about unharassed was curtailed, especially in Virginia.

Turner’s rebels killed between 55 and 65 people, at least 51 of whom were White before the rebellion was effectively suppressed on the morning of August 23, 1831. Turner survived in hiding for more than two months before he was captured in the Dismal Swamp and executed.

There was widespread fear after the rebellion. Militias, the first form of local police, were organized in retaliation to the rebels and to control the Black populous, often with violence.

Approximately 120 enslaved people and free Blacks were killed by Virginia militias and mobs in the area.

Virginia later executed an additional 56 enslaved people accused of being part of the rebellion and Black people who had not participated were also executed. Turner had been educated and literate as well as a popular preacher. The state legislature passed laws prohibiting education of enslaved people and free Black people, restricting rights of assembly and other civil liberties for free Black people, and requiring White ministers to be present at all worship services.

You may like

Virginia House Speaker To Keynote NSU’S 112th Commencement

Disbanding of TSU’s Board of Trustees: An “Attack On DEI”

THE PATH OF TOTALITY: If You Missed It, Catch Next One In 20 Years!

Virginia Beach’s 10-1 Election System Faces New Challenge

Hampton Roads Delivers Another Successful UNCF Mayors’ Masked Ball

Baltimore Bridge: A City’s Heartbreak, A Nation’s Alarm