Health

April Is National Minority Health Month

When Terrance Afer-Anderson was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010, he could have retreated from the world or crawled into a shell; instead he decided to build a bridge.

But Afer-Anderson is one of many in Hampton Roads who has helped to build bridges that connect underserved minority communities to quality healthcare. The point is this. As the nation observes National Minority Health Month in April by zeroing in on the theme: “Bridging Health Equities Across Communities,” try to envision the feat that Afer-Anderson actually performed after his doctor handed him a prostate cancer diagnosis seven years ago.

“My head more than my feet led me to the doctor’s office because the knowledge in my head told me to seek routine health screening,” said Afer-Anderson, who worked for the Norfolk Health Department for about two decades and retired in 2016. “This means I knew I needed to do my routine checkups and I did them,” said Afer-Anderson who developed the habit of going to the doctor for routine visits because he had asthma as a child.

While a 2016 Kaiser report showed that about 20 percent (17.2 percent) of all minorities are uninsured, Afer-Anderson has comprehensive health insurance. But at the time of his diagnosis, he also had a physician who always told him his health was fine. Changing physicians Afer-Anderson underwent several PSA tests and a rectal exam that showed he had prostate cancer.

In plain terms, the PSA test is a blood test that screens for prostate cancer. The test measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the blood. The PSA test detects a protein in cancerous and noncancerous tissues in the prostate, which is a small gland located below the bladder.

“During my biopsy for prostate cancer, everything was done pretty quickly within a couple of weeks,” Afer-Anderson said. “The diagnosis came back fairly quickly. No one knew what was going on with me until I received the diagnosis. Later, I told my support group what was going on in a regular meeting. When I told the group at a regular meeting about my prostate cancer diagnosis, Charlie Hill, a prostate cancer survivor embraced me physically and spiritually at the meeting. He became my big brother and mentor.”

In other words, Afer-Anderson did not resemble some minorities who are seeking health care. Afer-Anderson had health insurance that paid for routine health tests and ongoing care. He also had a habit of monitoring his health. More to the point, he did not suffer unduly like many minorities with critical health problems because the real problem, according to the groundbreaking 1985 Heckler report is that many minorities do not benefit “fully or equitably from the fruits of science or from those systems responsible for translating and using health science technology.”

In other words, the Heckler report said many minorities with serious health problems suffer unduly and disproportionately because many minority patients do not receive ongoing, high-end health care. But Afer-Anderson crossed the bridge that saved his life because he was able to pay for and receive ongoing, high-end treatment. During treatment, his highest PSA level dropped from a high of about 7.8 to a low of 0.01.

“That was not a high PSA level,” Afer-Anderson said of his earliest PSA level. “And this is the benefit of early detection. You get to choose your own treatment method. I chose my own method. And I haven’t had any of the side effects that men have with prostate cancer because I have been very blessed.” Specifically, the side effects of prostate cancer are frequent urination, lower back pain, and blood in urine.”

Afer-Anderson chose a treatment method called Brachytherapy. This means radioactive seeds or sources are placed in or near the tumor itself. This method delivers a high radiation dose to the tumor while reducing the amount of exposure from radiation to nearby healthy tissues. The term “brachy” is Greek for short distance.

“Because mine was not aggressive, I opted for something called Brachy therapy,” Afer-Anderson explained. “I did that because of my busy schedule and I only had to do it one time. I did this for six or seven months. It was done on an outpatient basis in the hospital and only took only about four hours. I went back to work two days later.”

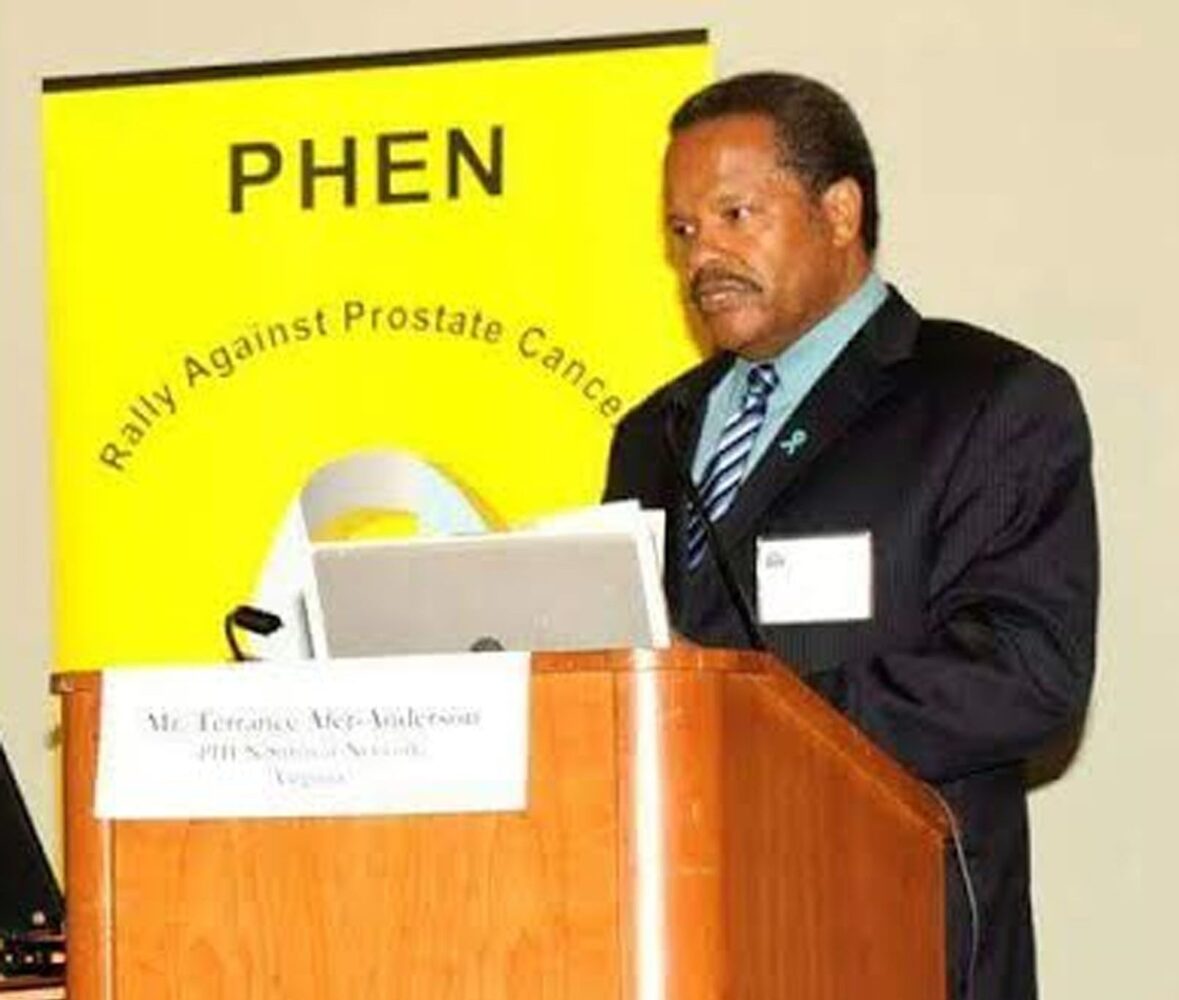

Soon, he was cured. More important, he continues to reach back to help others. Specifically, he was the chair of the public relations and marketing committee for the 2008-2011 African-American Men’s Health Forums. They were sponsored by the American Cancer Society (while he was still working at the health department and also undergoing treatment). Later, he joined the Prostate Health Education Network and moderated discussions on prostate education or served as master of ceremonies at consortium conferences in Washington, D.C.

In 2012, he launched a public health initiative called Illuminating Good Health Coalition. Co-sponsored by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities which provided the keynote speaker, the event attracted about 70 people. More important, 360 health screenings were done. Most recently, in August 2016 he received a $20,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to increase prostate cancer awareness. He is completing projects that will help close the disparity gap in minority neighborhoods.

♦♦♦

“The day that Charlie Hill hugged me in front of our support group, he told me he was drafting me into the army of prostate survivors,” Afer-Anderson said. “And I believed him.”

Afer-Anderson added, “Let me tell you how this works. That event I staged in 2012 – some men found their PSA levels were high. They were referred to physicians. I know of at least one incident where one man was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He said that if had not come to the event for free-screening he might have never known.

That event proved to be a bridge not just for that one man but for four to five other men who came and found they had elevated PSA levels.”

Afer-Anderson has built numerous bridges in minority communities because he believes in getting routine checkups. He also believes in linking and connecting others to health care. In a sense, his beliefs have helped more minorities face and also weather storms similar to those many workers encountered while building the legendary Golden Gate Bridge. Although the landmark bridge opened to the public in May 1937 and more than two billion vehicles have crossed it.

Bridge-building is not for the faint of heart because those who erected the expansive Golden Gate Bridge ran into frequent storms and encountered widespread opposition including skepticism from cost-wary city officials, skittish environmentalists and ferry operators who believed the new bridge would ruin their profits. Seasoned engineers, meanwhile, predicted that it was not only technically impossible to build the bridge, but the needed funding would be impossible to find during the beginning of the Great Depression. Ultimately, the bridge was financed by a $35 million bond issue, which was passed in California in 1930, according to news reports.

The point is this. Zero in on some of the obstacles that those real-life builders encountered on the Golden Gate Bridge. And it explains why Shannon Tooten, 29, smiles widely when she talks about the 250 low-income patients she has helped to receive free-or-reduced-medications in the past year at the Newport News Health Clinic, which retired Riverside Regional Medical Center administrator Golden Hill launched in 2010.

“Say, I have a patient who needs a prescription that will cost $25 or more,” said Tooten who has worked for about a year as a medication assistant caseworker at the Newport News Health Clinic.

“I can go on the data base and get it at a discount through a preferred network,” said Tooten, who was treated as a patient at the Newport News Health Clinic before she became an employee. She visited the clinic to obtain a birth control implant device. There, administrators linked and connected her to health care providers who provided their services at reduced prices.

Tooten said, “So I understand how it feels when I tell a patient how to buy a prescription at a free or reduced price. Some of them leave me saying, ‘I feel so much better now.’ In some cases, I have helped patients get a prescription that will cost them only $25, after I go on the data base and help them get a discount through a preferred network.”

In other words, like thousands of anonymous workers built the legendary Golden Gate Bridge, the same applies to numerous health-care workers in Hampton Roads including Wooten who works behind the scenes at the clinic to help build a bridge for underserved minorities.

Tooten’s tech-savvy skills and personal experiences are helping to ease the (disproportionate) level of suffering that many minorities with health problems routinely encounter, as the 1984 Heckler report noted. But the ground-breaking Heckler report was published over 30 years ago.

“I like being a bridge that helps others gain access to free or reduced medication,” Tooten said. “I have the ability to use the internet for patients who don’t have the internet or a smart phone. I am the middle man to better health,” she added, smiling widely.

Wooten said, “It makes me feel warm inside when I help others. For example, I have a Hepatitis C patient who needs medication (Harvoni), which costs $30,000 for 12 weeks.”

According to news reports, Harvoni had a more than 95 percent success rate in a recent study on 865 patients with various types of Hepatitis C. Those who received Harvoni once daily for 12 weeks were cured.

Describing the bridge that she helps to build at her office computer every single day in the clinic in Newport News, Tooten said, “I was able to help the patient get the medication (Harvoni) for free. He thanked me so much. They were going to deliver it but it is so expensive that they needed a signature before they would deliver the prescription. I called him and told him. He did what was necessary and received his medication. He is so happy. He said he is blessed. Oh yes, some of our patients visit our clinic and later make donations.”

Tooten is in her 20s. So she does not have any serious health problems. Still, she feels uplifted after she links and connects others to equitable health care. “I don’t have any special health issues like high blood pressure, cholesterol, or diabetes,” Tooten said. “Still, I would say I’ve helped about 250 patients in a year to get free or discounted prices on medication.”

Next Week – Part Two – How a Newport News Clinic and a Retired Doctor are Building Bridges that are Helping Many.

By Rosaland Tyler

Associate Editor