Black History

An NJG Series: Our History, Our Journey – Part III: Black-Owned Hotels In Norfolk

From the early 1900s through the mid-20th century, Norfolk’s Black-owned hotels formed the backbone of the Church Street business district, offering safety, dignity, and opportunity during the Jim Crow era while shaping a vibrant community known as Norfolk’s own “Black Wall Street.”

#BlackHistory #NorfolkVA #ChurchStreet #BlackWallStreet #JimCrowEra #BlackEntrepreneurs #HistoricNorfolk #PlazaHotel

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter Emeritus

New Journal and Guide

From 1907 to the early 1950s, three Black-owned and operated hotels existed in the Church Street Business Corridor.

These three prime outlets were among the businesses which made up Norfolk’s “Black Wall Street,” like the historic enclave in Tulsa, Oklahoma destroyed by White rage in 1929.

But in Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News, Richmond, Petersburg, and Hampton, they continued to thrive until African-Americans overcame the walls of Jim Crow.

Black-owned hotels during the Jim Crow era were necessities to stage parties, conferences, or places to spend the night while visiting or working in the city, and Black entrepreneurs found them financially lucrative.

Lemuel “Lem” Wesley Bright, opened the first significant Black-owned hotel in Norfolk, The Mt. Vernon Hotel (later named The Wheaton) in 1907. Over a decade later, William H.M Tatum opened the Tatum Inn and another enterprising Black man, Bennie E. Davis, opened the Prince George Hotel at Church and 18th Streets.

Bonnie McEachin later bought the Prince George, running the last Black-owned hotel in the city, even after Jim Crow.

◆◆◆

In an article in the February 25, 1933 edition of the Guide, a headline announced “Prince George Hotel is Now Open at Church and 18th Street” and “provided Norfolk with another Colored Hotel.”

It had been open for two weeks.

The hotel was formerly known as the Hague, and its proprietor and manager was Bennie E. Davis and B.F. Johnson ran the grill and dining facilities.

The Hague was built for Whites for the Jamestown Exposition in 1907 Sewells Point.

Davis was also the manager of the “Plantation Beach.”

Like the Wheaton and the Tatum Inn, the Prince George was a three story brick structure and had “hot and cold running water in each room.”

It has 24 rooms and 18 of them were double rooms and six single, with seven baths, scattered about on all three floors. With a capacity for 74 guests, the hotel had maids and bell-boys to serve patrons who paid $1.00 per day and up for transient guests and $2.00 by the week.

In a July 29, 1944 edition of the Guide, an article reported The Prince George Hotel, was taken over by the United Seamen’s Service (U.S.S) to house Black Merchant Seamen on July 17.

It accommodated 50 Seamen on leave in Norfolk and it was renamed “The U.S.S Prince George Hotel Residential Club.” An Executive Committee was formed to oversee the operation of the facility which included Attorney J. Eugene Diggs and Guide Publisher, P.B. Young Sr., among other local big-wigs.

According to a November 10, 1945 edition of the Guide, with WWII ended, the hotel reverted back to civil control on October 3.

Bennie E. Davis and his original management team resumed control of the hotel’s day-to-day operations.

According to a June 20, 1951 edition of the Guide, after six years of financial stress Davis and his partners, sold the hotel to Bernard Glasser and Associates for $23,000, at an auction after the owner of the property Robert D. Ruffin, defaulted on the first deed of trust.

Davis, who had leased the property from Glasser for six years, would continue managing the facility until Glasser sold it to Mrs. Bonnie McEachin.

◆◆◆

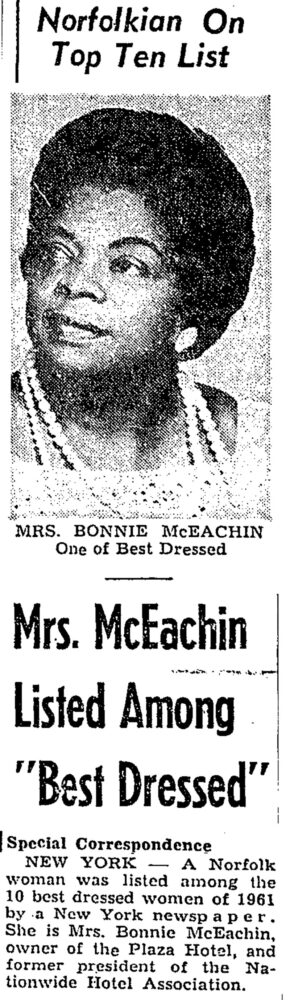

McEachin hailed from Rose Hill, North Carolina, according to a May 1, 1995 edition of the Guide in an article headlined: “Remembering the Past: “Norfolk Businesswoman remembers Grand Plaza.”

She followed her husband, Graham who arrived in Norfolk first to attain work. When she arrived, McEachin landed a job at the Shalimar Grill where she worked briefly on Church Street.

The work was too arduous and too noisy, she said. So, she ventured out into a field more suited to her talents: hospitality. She bought a 12-room structure at 1112 Church Street in 1949 and converted it into a rooming house named the “Plaza House.”

“I always liked people, always wanted to meet people and always wanted to operate a hotel or something like it,” she is quoted in the article.

When the Princess George Hotel was sold to Glasser Associates, overtures were made to sell it to her, but she said she was not ready initially.

In late 1950 for $1,000 a month, she leased The Prince George Hotel and renamed it “The Plaza Hotel” a year later when she formally purchased it.

She invested heavily in upgrading it. The Plaza also served as a base for her highly successful catering business.

Like the other hotels operating at the time, The Plaza was a venue for parties and conferences.

Her reputation resonated nationally as McEachin was named the “Nationwide Hotel Association’s Hotel Women of the Year” in 1955. Deemed one of the 10 best dressed Black women in the country, in 1961 McEachin was a charming and outgoing hostess, she engaged with popular Black entertainers and sports figures who visited Norfolk.

She used all of her charms and business savvy to compete for patrons with the aging Wheaton and Tatum Inn.

Virginia’s strict Jim Crow laws forbade hotels from housing Black and White patrons together. But McEachin ignored them, for Black entertainers and bands had White members and managers.

As Jim Crow’s grip was lessening, she had to compete with White hotels, along with the Wheaton and the Tatum, too, she noted.

By the mid-1950s, the Wheaton and the Tatum were razed to make way for redevelopment of the St. Paul’s/Church Street business corridor. In their place was the Young Park Public Housing community.

No longer deterred by Jim Crow, instead of Church Street businesses, Black began patronizing White-owned ones.

The Plaza was not directly impacted by the re-development and operated until a fire nearly destroyed it in 1980.

That spelled the end of Black hotel ownership in Norfolk and Norfolk’s version of Black Wall Street.

In a May 23, 2001 edition of the Guide a story detailing that Donnell Thompson, the CEO of Thompson Hospitality LLC in Chapel, Hill, North Carolina, had received permission from the city to build an “Extended Stay” hotel complex at the southeast corner of Corner of Granby and City Hall Avenue south of the Federal Building.

The Dominion Enterprise Building is in that space today.

Black History1 week ago

Black History1 week ago2026 Black History Month: A Century Of Black History Commemorations

Hampton Roads Community News6 days ago

Hampton Roads Community News6 days agoCommemorating A Norfolk Booker & Her History-making Service Career

Religion6 days ago

Religion6 days agoFaith Leaders Standing in the Gap

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoGrammys Open Black History Month as Michael Jackson’s Story Heads to the Big Screen

HBCU4 days ago

HBCU4 days agoVUU Centennial Musical To Highlight Black History Journey

Civil1 week ago

Civil1 week agoThe Black Press Of America Stands With Don and Fort

National Commentary1 week ago

National Commentary1 week agoGuest Publisher: What We Can Learn From The People of Minnesota

National Commentary7 days ago

National Commentary7 days agoAlex Pretti and Renee Good Were Lynched. How Will We Respond?