Black History

An NJG Series: Our History, Our Journey – Part I: Black-Owned Hotels In Norfolk

During segregation, thriving Black-owned hotels such as the Mt. Vernon/Wheaton Hotel, the Plaza Hotel, and others on Norfolk’s Church Street provided safe lodging and dignity for African Americans excluded from white-only establishments — and for a time, Church Street stood as a vibrant “Black Wall Street” in Hampton Roads.

#NorfolkHistory #BlackBusiness #ChurchStreet #JimCrow #BlackWallStreet #SegregationEra #BlackEntrepreneurs #HistoricNorfolk

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter Emeritus

New Journal and Guide

The “Separate but, Equal” or Jim Crow era, in America, did not stop Blacks from accessing resources and creating facilities to house, educate, employ, or entertain themselves.

African-Americans developed neighborhoods, business districts, schools, and recreational venues when by law, they were barred from facilities reserved for “Whites Only.”

These racially and economically “separate” communities, necessitated the genesis of a network of “Black Wall Streets” not only in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but all over the nation where large populations of Blacks lived and practiced communal and economic cooperation to survive.

Hampton Roads was no exception. Norfolk’s Church Street business district saw Black entrepreneurs create spaces for practicing professionals such as lawyers, pubs, theaters, retail shops and even hotels.

Blacks visiting the city for business, families seeking shelter overnight; sports teams and individuals were hard-pressed to find a hotel especially in the Jim Crow south and parts of the north.

Crowded rooming houses or an extra bedroom in a relative’s home or sleeping along the roadside were humiliating options.

But several hotels of varying sizes were developed in the Norfolk Church Street business district.

The Guide Archives reveal the presence of the more prominent, Black-run facilities from the early 1900s to the mid-1950s, before redevelopment and desegregation ended their existence.

Paid display advertisements and stories about the hotels, and the people who ran them, appeared on the pages of the Guide. There were references to the hotels in the Green Book, a nationally distributed travel guide for Blacks seeking welcoming hotels, gas stations, and restaurants. There were also records of local insurance firms.

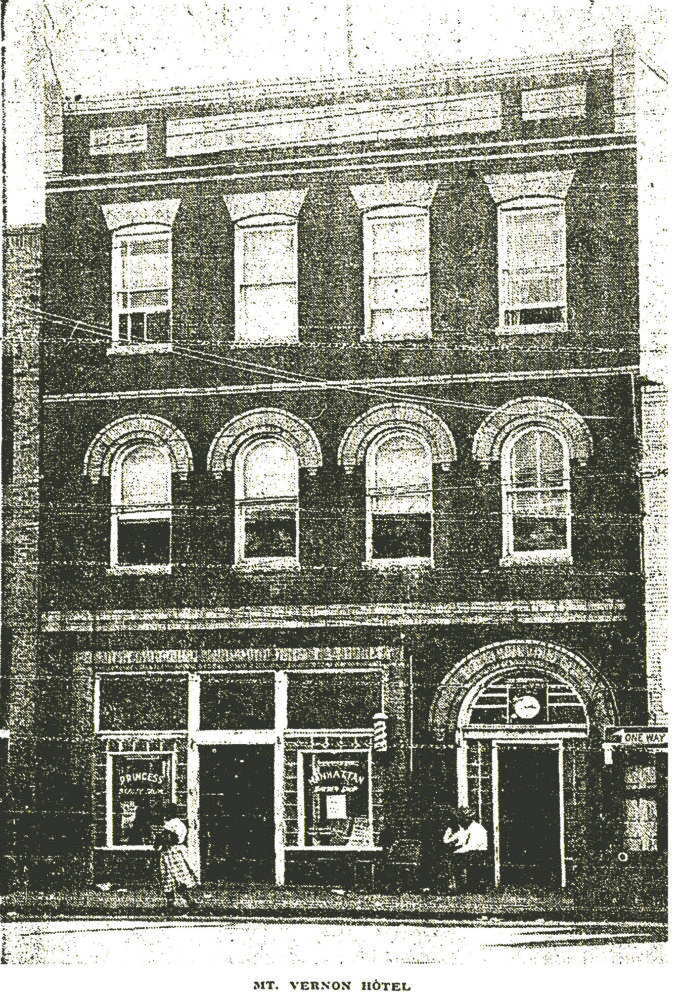

The storied list includes the first Black-owned and commercially equipped Mt. Vernon Hotel, which was later named the Wheaton Hotel at 633 Brambleton Avenue. The Norfolk Whole Florist is located there now.

There was The Smith Hotel at 716 Smith Street; the Huntersville Hotel at 1634 Church Street; the Tatum Inn at Charlotte and 435 East Brewer Streets and the Prince George Hotel. Later it was named the Seaman’s Hotel before it was named the Plaza Hotel at corner of Church and 18th Streets.

During the Jim Crow era, there were also small single-family housing structures, which were called “hotels” or boarding houses.

Apart from the legacy of the hotels, the entrepreneurs who acquired the managerial skills and resources to build and operate them are fascinating, too.

The one feature they had in common, according to profiles in the Guide, was their ability to attain business skills, moving from one money making venture to the next, amassing capital and investing it in the next one.

The presence of several Black-owned banks at the time also helped.

Lemuel “Lem” Wesley Bright, who died in 1924, 14 years after he opened the Mt. Vernon Hotel, was a good example. He was born in Norfolk on October 3, 1870.

In an October 3, 1953, edition of the Guide, his hotel in its final days, was called a “landmark” in a profile of his life. The article said Bright received much of his business acumen from his father, who was a successful merchant in his own right.

The young Bright bought a horse and wagon to work in the ice delivery business. But the larger ice companies fearing competition shut him down.

He then secured a job as a bar keeper at a “saloon” owned by Church Street businessperson and former council member Charles Egts before 1900.

Bright invested his earnings in starting a restaurant and boarding house prior to building the Mount Vernon Hotel.

After several years of construction, in 1907 the Mount Vernon Hotel opened at 353 Queen Street (later re-addressed as 633 E. Brambleton Street) near the intersection with Church Street.

The hotel was defined as “the most modern and commodious hostelry for Colored people in the United States.”

Bright, deemed as one of the “most active businessmen” in Norfolk, was involved in other endeavors, including manager, and part owner of the Mount Vernon Market.

By 1916, he directed his attention to real estate. He bought a patch of bay front land between Willoughby Spit and the new Naval Operating Base (NOB) and named it “Little Bay Beach.”

Beaches in Tidewater at that time were segregated, and it was the only resort opened to Blacks for two decades before Seaview Beach was opened.

His family and business associates managed the hotel, while Bright concentrated on his real estate ventures.

According to the November 9, 1924, edition of the Guide, Bright died November 22, 1924, after a prolonged period of declining health at his home at 312 Bute Street. His obituary noted that he was a leader of the members of the St. John’s AME Church, Hiram chapter of the Royal Arch Masons, Rising Son Lodge, A.F. and A.M., Elks, Sons of Norfolk S. & B. Association, and the Aeolian Club He is buried in the Bright Family Lot in West Point Cemetery.

After Bright’s death, the Mount Vernon was purchased by Norfolk attorney J. M. Harrison. The new proprietor was experienced in the hotel industry nationally. He rechristened the facility as the “The Wheaton Hotel,” in memory of J. Frank Wheaton of New York, the former Grand Exalted Ruler of the Elks. The hotel became associated with the Elks, according to the Guide Archives.

By 1940, Bertram Brown purchased the hotel and was listed in the 1940 Norfolk Directory as providing “furnished rooms.” Brown’s widow, Devetta Morris, continued to operate the hotel through the 1950s (NJG 1953).

In 1953, the front 40 feet of the hotel were removed during the widening of Brambleton Avenue. By 1960, the remainder of the building was demolished during redevelopment efforts in the Church Street and St. Pauls areas, undertaken by the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NRHA) according to the Guide.

Part II: The Tatum Inn and its Enterprising Founder

Local News in Virginia1 week ago

Local News in Virginia1 week agoTony Brothers: In The Zone

Black History1 week ago

Black History1 week agoMaking History Again During Women’s History Month

HBCU1 week ago

HBCU1 week agoCharlie Hill Makes Historic Gift Of $1.5M To VSU

Black History1 week ago

Black History1 week agoVirginia Women Who Shaped— And Won— Fight For Voting Rights

Local News in Virginia1 week ago

Local News in Virginia1 week agoBridge Corner – 3.5.26

National Commentary1 week ago

National Commentary1 week agoThe War of Choice

Black Church5 days ago

Black Church5 days agoSuffolk Church Grows Produce Indoors And Gives It Away Free

Civil1 week ago

Civil1 week agoDigital Download: Not All A.I. Is Created Equal