National News

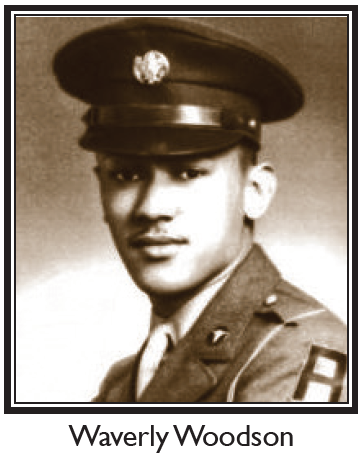

75 Years Later: New Efforts To Honor Black Hero

By Leonard E. Colvin

Chief Reporter

New Journal and Guide

Seventy-five years after his heroic efforts, there are new efforts to award Corporal Waverly B. Woodson the Medal of Honor for bravery on D-Day during WWII.

Woodson died in 2005, but his widow who lives in Maryland, is working with U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen (D) of Maryland, who has petitioned the Secretary of the Army to have Woodson so honored.

According to a recent story by the Associated Press, a document found by Linda Hervieux, a journalist who wrote a book about the Black soldiers who took part in D-Day, is giving a resurgence of interest to Woodson.

In her book, “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and at War,” Hervieux used documents from the Harry S. Truman Library that mention Woodson’s bravery. It is believed to be the piece that will help Woodson’s widow’s cause.

However, the first time Woodson’s story was featured was in the Black Press which covered World War II stories of Black soldiers and sailors fighting for democracy abroad in a segregated armed forces. On December 15, 1945, the Norfolk Journal and Guide carried a story headlined “Veteran Awaits War Medals Promised But Never Awarded,” which sheds lights on Woodson’s frustration 75 years ago.

On June 6, 1944, Allied forces invaded beaches along the Normandy Coast in southern France to wrest Europe from the grip of Nazi Germany.

Although he was an Army Medic, Woodson was assigned to the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion on Omaha Beach, where U.S. forces landed.

The unit was tasked with sending up balloons equipped with explosives to deter German planes from attacking invading troops on the beaches.

He was wounded, but for 30 hours, according to military records, he saved the lives of dozens of fellow soldiers.

Senator Van Hollen has noted that the reason why Woodson was denied the medal was that he was African-American.

Woodson was a native of Philadelphia and had graduated from Lincoln University, an HBCU, before enlisting in the Army.

Instead of receiving a commission as an anti-aircraft officer, the Army said it had too many and he was relegated to being a medic.

He was among many other Black soldiers who served valiantly on D-Day or in other theaters of action but were not honored by racist white officers for their efforts.

At the time the 1945 story ran, Woodson was 23-years-old. He had been discharged from the military a month before on November 13. At one point before his discharge, Waverly Woodson’s exploits were recounted, according to the GUIDE story, “on a coast-to-coast radio broadcast.”

The GUIDE story reported that Woodson was “wounded by a shell fragment but continued to administer first aid to at least 250 casualties on the shell and bomb-raked beach.”

“For his meritorious duty on the Normandy Beach, Sgt. Woodson,” the GUIDE story said, “was recommended for a Distinguished Service Medal (DSM), the third highest award given by the United States.”

“The recommendation was later held up by Sgt. Woodson’s Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. Leon J. Reed, a white officer from Kentucky until it was too late for action to be taken on the Matter.”

Instead of the Distinguished Service Medal, Woodson was promised the Bronze Star which ranked eight in order of importance.

But “To add insult to injury,” according to the GUIDE article, “Sgt. Woodson has never … officially been given” the medal.

He received a War Department citation entitling him to the medal but the ceremony necessary for the actual award was never held.

In fact, he was told the ceremony would be bestowed upon him in France, then England, the United States, and Hawaii and then “the United States again.”

Along with the Medal of Honor, he was entitled to wear 10 others, including the Good Conduct Medal.

After the Army, Woodson had a career in medical technology and worked at the Naval Medical Center at Bethesda, Maryland.

According to the Senator’s letter, the U.S. Army has refused to review Woodson’s case to date because it lacks an original award recommendation.

υυυ

Although the mainstream media and Hollywood at the time, ignored their role, the African-American Press led by the Norfolk Journal and Guide and other Black publications recorded this history during that time for people then and today.

Throughout WWII and especially D-Day in 1944, the Black Press dispatched reporters such as the GUIDE’s John Q. ‘Rover’ Jordan, P.B. Young, Jr. and Thomas Young, Lem Graves and the ANP’s (Associated Negro Press) Joseph Dunbar to the European and South Pacific War Zones to cover the exploits of the Black soldiers.

Back home the Black press covered the impact of the war on Black families, such as Black Gold Star Mothers who lost their sons but supported the war effort in various ways.

U.S. Army history records the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion where Woodson served as the only combat unit composed of Black troops to see action on Normandy Beach on June 6. It concedes other Black support and technical units landed shortly afterward.

But, according to a June 23, 1944 edition of the GUIDE, an article “Review Combat History of First Negro Unit to Land in France,” contradicts that assertion.

It reads, “Since June 6, 1944, men of the 582nd Engineer Dump Truck Company have been in the thick and thin of the Normandy and German campaigns.

“They made up the first company of the initial assault forces to land on the Utah Beach and they were the first Negro troops to touch European soil … on D-Day …”

The unit not only cleared and removed thousands of mines laid by the Germans to fend off Allied land forces, but they also transported supplies to the troops on the front lines.

Also, the Black soldiers devised an ingenious taxi system, where they transported troops to the front and retrieved wounded servicemen, carrying them back to the beaches to be placed on amphibious units to return them to waiting ships,

A good example of a Black man being honored for his D-Day efforts at Normandy was First Sergeant Norman Day of Danville, Illinois. His story appeared on June 23, 1945 in the GUIDE under the title “Review Combat History Of First Negro Unit To Land In France.”

Day, who directed traffic on the beach, was “singled out by a British General and was awarded the British Distinguished Service Medal,” according to the article. He also saved the life of an American Lieutenant Colonel by administering prompt first aid when a Nazi bomb landed on the area. The bomb killed six infantrymen.