Hampton Roads Community News

Two Generations of Butts Women

By Rosaland Tyler

Associate Editor

New Journal and Guide

Norfolk native Evelyn T. Butts highlights this year’s theme for Women’s History Month: Visionary Women; because she had a habit of opening and leaving a door open.

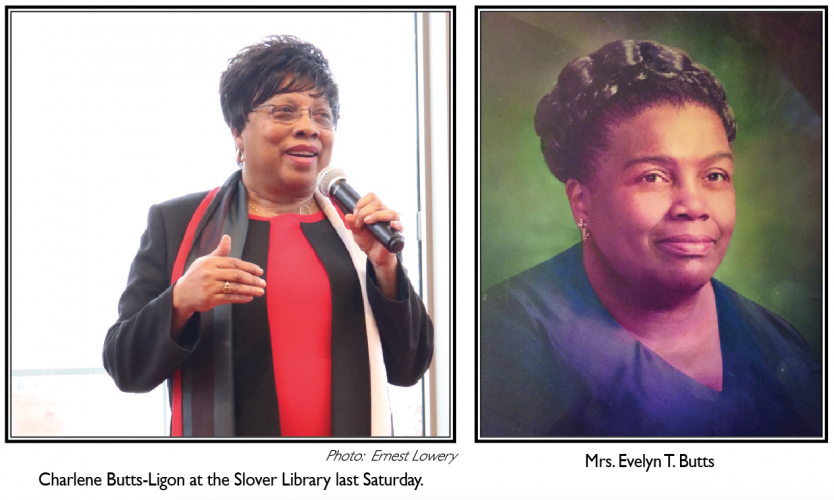

Butts did not formally pass the torch on to her youngest daughter, Charlene Butts Ligon. She recently stood in the Slover Library autographing copies of her 2017 book on her mother, “Fearless: How a Poor Virginia Seamstress Took on Jim Crow, Beat the Poll Tax and Changed The City Forever.”

But scroll through her daughter’s website. While you will not see a photo of the mother and the daughter exchanging the lighted torch that ancient Greek runners passed before a major contest. You will see the author standing in photographs with several well-known public advocates including Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, Former Interim Democratic National Committee Chair Donna Brazile, and American Urban Radio Networks Washington Bureau Chief April Ryan.

The point is her mother did not pull her daughter aside and hand her the legendary torch. Instead, her mother set an example by tirelessly blazing a trail through a maze of discriminatory laws. This means that from the late 1950’s until her death on March 11, 1993, the mother blazed a path by taking firm hold of a closed door. For example, her mother launched the landmark lawsuit that challenged the mandatory $1.50 poll tax. While the court dismissed the first lawsuit, the Supreme Court ruled that the mandatory $1.50 poll tax was unconstitutional in 1966 in the second lawsuit.

Ligon, who was six when the Supreme Court handed down its decision, notes in her book, “In some ways, researching my mother’s life has made me think about her in ways I had not while I was growing up under the same roof. Who was Evelyn Thomas Butts? What gave her such confidence? How could she be so determined when she was beset with never-ending problems, both personal and in her community? Where did her incredible strength come from?

Ligon, and her sister, Jeanette Brinkley provide the answers. They began to collect material for the book in 2007, four years after their oldest sister Patricia Stevenson died. In 2017, Ligon’s sister Jeanette died from diabetes and heart disease. Ligon buried her sister and continued to write the book.

In a sense, it describes what happened after her mother made history by opposing the state’s mandatory $1.50 poll tax. The Supreme Court voted 6-3 to eliminate the poll tax in March 1966. Two and one-half years after her mother wrapped up that historic contest, she helped launch voter registration campaigns in Norfolk, first in her own Oakwood neighborhood and then citywide.

Her mother helped establish the Concerned Citizens for Political Education, which soon became the most influential African-American political organization in Norfolk during the 1970s.

In other words, the Supreme Court ruled on her mother’s historic lawsuit. Two years later her mother was opening more doors. Specifically, in 1968, members of Concerned Citizens for Political Education helped elect Joseph Jordan to Norfolk’s city council, its first African-American member. The next year it helped elect William P. Robinson, the first African-American ever to represent Norfolk in the House of Delegates. Butts became influential in local politics to the point that the press often called her one of the most powerful African-American politicians in Norfolk by the end of the 1970s.

About two decades later, the city of Norfolk on Nov. 18, 1995 renamed Elm Street to honor her mother. In February, Hampton Roads Transit named the Evelyn Butts Transfer Station in her honor.

“If you are not persistent you can’t get things done,” Ligon said of her mother’s legacy. “Some people are deterred by obstacles but I know people who are focused and get things done. There is always some type of roadblock or obstacle in life. But the older I become, the more I am convinced that you have to stay there and keep moving forward. I am sure I inherited this trait from my mom. If you told her no she would go away and try to figure out how she could get what she wanted.”

Ligon, who retired as a U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. in 1995 after 20 years of service, said, “At a young age, I went a lot of places with my mother – to the courts and to meetings. I remember so many of the things that my mother did because I was there.”

Ligon added, “She was showing me the ropes without me realizing it. As I watched my mother, I became more involved in civic activities. I can remember talking to some of my friends in junior high about what was going on in my home. They would look at me as if I was from another world. What was always on my mind was what was going on in the community. The things we needed to do to move on as African-Americans. No, my mother didn’t ceremoniously pass the torch on to me, but she passed it.”

Ligon lives in Bellevue, Neb. with her husband Robert. She has served as secretary of the Nebraska Democratic Party since 2009. She has three adult daughters.

Instead of trying to explain why Butts and her daughter are visionary women, review the checklist for this year’s theme, Visionary Women: Champions of Peace. To qualify, a woman must have resolved conflicts in her home, schools, and community, according to the National Women’s History Alliance website. She must have consciously built supportive, nonviolent alternatives and loving communities, and advocated change. She must have given voice to the unrepresented and hope to victims of violence and those who dream of a peaceful world.

Asked if her perspective matches her mother’s, Ligon said, “I would say yes. I have the same drive. I never considered my mother a traditional person who played a traditional gender role in our family. I am sure that is why I went in the military, a mother with two children. It took courage for me to go through that. I think I inherited my mom’s courage. Obama was running for office when I started working on the book.”

Ligon is also involved in voter registration in Nebraska. “I wanted to make a difference,” she explained. “I was kind of following my mother’s footsteps. I felt I wanted to make a difference. I did. I have leadership skills that I’ve never thought about but believe I inherited them from my mother. She was a leader. She was the one who always got all of the ladies together. It was never a small group of ladies. It was always a lot of them. She wanted to make a difference. She believed in America and wanted to make it better. She believed everybody should have a fair shot. I believe that too.”

In her book, Ligon said her mother was compassionate and kind. The spotlight mattered less than opening doors, eliminating racial injustice, and improving adjacent lives. She always aimed to help others. Pointing to her mother’s many accomplishments including how she helped create Rosemont Middle School, picketed Be-Lo Supermarket because it only hired African-Americans for janitorial and stocking positions, and organized a group that protested segregated seating at Foreman Stadium.

Ligon said, “She was able to help people get help.” The political was frequently personal, in other words. Ligon, who attended Rosemont Middle School from grades 5-9 and enrolled at Norview High, said, “The reason they built Rosemont – which started with modular buildings, no cafeteria, library, or principal – was to keep me and the majority of children in our neighborhood from attending Norview Elementary.

The same applied to the picket that her mother organized at Be-Lo Supermarket. “They picketed because they would only hire African-Americans as stockers or janitors. They would let an African-American woman run the cash register when it got really busy but they wouldn’t pay her a cashier’s salary,” Ligon said.

The supermarket obtained an injunction that prohibited picketing because the civic group was not a labor union, Ligon said. In the end, “They did end up hiring more African-Americans,” she added. “The civic group organized car pools to take people to other stores to shop since the majority of people walked to Be-Lo. Ms. Josephine, (the African-American stocker), got promoted.”

Regarding the picket at Foreman Field, Ligon said, “Foreman Field had a colored section. I don’t know if there were signs or not but it was understood. I have a photograph that shows me at age 12 (1960) carrying a picket sign.”

Still, her mother blazed a trail through a maze of discriminatory laws and customs because she was compassionate and kind, Ligon explained. That is how she became a trailblazer. “I think at the end of her life she became somewhat aware of her impact. But I don’t think she realized the totality of her impact on the state and nation. My mom’s lasting legacy is the idea that people should get out and vote, every vote counts – that never fails. That still matters. It still makes a difference. One vote does count.”

To order her book and receive a special discount during Women’s History Month, please phone 402-215-1571. You can also order the book online.